Mastering Tones in Chinese A Practical Pronunciation Guide

Tones in Chinese are the secret sauce of the language. They’re the different pitches you use when saying a syllable, and they're what give words their meaning. A simple sound like ma can mean "mother," "hemp," "horse," or "to scold"—it all comes down to the tone. Getting these pitches right is your first major step towards actually speaking and understanding Mandarin.

Why Chinese Tones Are Your Greatest Ally

For a lot of learners, the whole idea of tones in Chinese feels like the biggest wall to climb. It’s easy to see them as this extra, frustrating layer of complexity you just wish wasn't there. But what if you flipped that thinking? What if you saw them not as a roadblock, but as your single greatest tool for speaking clearly?

Think of it like this: tones are the melody of Mandarin. Without a melody, a song is just a random collection of notes. In the same way, without tones, Mandarin syllables are just sounds without any real meaning. They aren't an optional extra; they're woven into the very fabric of the spoken language.

Tones Create Meaning

In English, we use our pitch to add emotion or ask a question. The difference between a flat "Great." and a rising "Great?" is all in the intonation. Mandarin takes that concept and bakes it into the core of every single word. The tone isn’t just for colour—it literally defines what the word is.

This brings us to the classic example you’ll hear everywhere: mā, má, mǎ, mà. The consonant and vowel sounds are identical, but their meanings are worlds apart, all thanks to the tones:

- mā (妈) means mother.

- má (麻) means hemp.

- mǎ (马) means horse.

- mà (骂) means to scold.

Imagine trying to talk about your horse but accidentally telling someone about your scolding mother. It sounds funny, but it happens! While native speakers can sometimes figure out what you mean from the context, getting the tones right is what separates confusing, broken Mandarin from clear, confident communication. A wrong tone is like a spelling mistake that changes the entire word.

Here's the key mindset shift: stop thinking of tones as something added to a word. The tone is an inseparable part of a word’s identity, just as much as its vowels and consonants.

Your Roadmap to Tonal Intuition

This guide is all about helping you build real, intuitive control over tones, not just memorising a bunch of abstract rules. We're going to break down each tone one by one, look at how they change in real conversation, and give you practical drills to build that crucial muscle memory.

Instead of fearing tones, you'll learn to hear them, feel them, and use them correctly. By reframing your approach, you'll find that mastering the tones in Chinese is the most direct route to being understood and speaking with genuine confidence. Let's get started.

Alright, let's get into the nuts and bolts of Mandarin's four main tones. Now that you know why they're so critical, it’s time to actually meet them. Think of this as your first real workout. We're going to ditch the dry, academic definitions and connect each tone to a sound you probably already make in English.

Each tone has its own unique musical shape, or pitch contour. Getting a clear mental picture of this shape is half the battle. You need to hear it in your mind's ear before you can say it. This is exactly why a solid grasp of Chinese Pinyin is so helpful—it gives you the visual cues you need to connect the sound to the symbol.

To make things a bit clearer, here's a quick look at all four tones side-by-side.

The Four Mandarin Tones At a Glance

This table is your cheat sheet. Use it to quickly compare the pitch, feel, and a simple example for each tone.

| Tone | Pitch Contour | Analogy | Example (Pinyin) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Tone | High, Level | A steady hum | bā (八 - eight) |

| 2nd Tone | Mid, Rising | Asking "What?" | fú (福 - luck) |

| 3rd Tone | Dipping, Rising | A vocal valley | hǎo (好 - good) |

| 4th Tone | High, Falling | A sharp command | kàn (看 - to look) |

Now, let's break down what's actually happening with your voice for each of these.

The First Tone (一声 yī shēng): The High and Level Hum

Imagine a doctor asking you to open your mouth and say "ahhh." Your voice comes out high, flat, and steady, without any dips or rises. That's the first tone, dead on.

- Analogy: A steady, high-pitched hum or holding a single note while singing.

- Pitch Contour: It starts high and stays high. Just a straight, flat line at the top of your comfortable vocal range.

- Example: mā (妈), meaning mother. Your voice should hold that high, level pitch all the way through the sound.

The Second Tone (二声 èr shēng): The Questioning Rise

This one feels pretty natural for English speakers. It's the upward slide you use when asking a genuine question. Think of the sound you make when you say, "What?" or "Really?" in complete surprise.

- Analogy: Asking a question, like "You're leaving?"

- Pitch Contour: It starts in the middle of your range and rises smoothly upwards. It’s like drawing a diagonal line up from left to right.

- Example: má (麻), meaning hemp. Start at a comfortable mid-level and let your voice climb as if you're waiting for an answer.

The Third Tone (三声 sān shēng): The Dipping Valley

This is often the one that trips learners up the most, but it’s not as scary as it looks. The third tone goes down, then comes back up. It starts low-ish, drops to the very bottom of your range, and then rises again.

The third tone is the only one of the four main tones in Chinese that changes direction mid-syllable. It’s like tracing a small 'V' shape with your voice.

- Analogy: Tracing a valley with your voice—down one side and up the other.

- Pitch Contour: It has a falling-rising shape. It begins mid-low, bottoms out, and then climbs back up.

- Example: mǎ (马), meaning horse. You'll find it has a longer, more drawn-out sound compared to the others.

The Fourth Tone (四声 sì shēng): The Sharp, Decisive Drop

Finally, we have the fourth tone. It’s short, sharp, and to the point. Think of giving a firm command, like "Stop!" or "No!". It's a quick, forceful drop from a high pitch straight down to a low one.

- Analogy: A sharp command, like "Hey!"

- Pitch Contour: It's a falling tone. It starts high and drops decisively to the bottom of your range. No hesitation.

- Example: mà (骂), meaning to scold. Say it fast and firm, like you mean business.

Getting these four shapes right is absolutely fundamental. Consistent weekly practice is crucial for students to correctly hear and produce tones in real-time, as the tonal nature of Chinese requires sustained study time to master.

How Tones Change In Real Conversation

If you only ever practised tones in Chinese on single syllables, you'd be in for a real shock when you jump into a conversation. In the flow of natural speech, tones don't live in a vacuum. They bump into each other, adapt, and shift their shapes in a process called tone sandhi.

This isn’t some obscure grammatical footnote for advanced students; it’s a core part of spoken Mandarin that you'll hear and need to use from day one. Getting these changes right is the secret to moving beyond stilted, robotic pronunciation and developing a more fluid, natural-sounding accent. Think of it as learning the real rhythm and melody of the language.

The Most Important Rule: Third Tone Sandhi

Let's dive into the most common and critical tone change you'll encounter: the third tone sandhi. The third tone, with its dipping-then-rising contour, is already the most complex one to say. Now, try putting two of them back-to-back. It’s awkward, slow, and just doesn't feel right.

To fix this, Mandarin has a simple, elegant rule: when two third tones are next to each other, the first one transforms into a second (rising) tone.

This is exactly why the most famous Mandarin greeting, nǐ hǎo (你好), which is technically two third tones, is almost always pronounced ní hǎo. Listen for it: the "nǐ" (你) rises instead of doing that full dip.

Rule of Thumb:

Third Tone + Third Tone → Second Tone + Third Tone

This shift is so automatic for native speakers they don't even have to think about it. For us learners, consciously applying this rule is one of the fastest ways to sound more authentic.

Applying The Third Tone Rule In Practice

This isn't just a one-off trick for "nǐ hǎo." This rule is everywhere. Let’s look at a few more examples to see it in action:

- hěn hǎo (很好) – "very good" becomes hén hǎo.

- kě yǐ (可以) – "can" or "may" becomes ké yǐ.

- shuǐ guǒ (水果) – "fruit" becomes shuí guǒ.

One crucial detail: the Pinyin spelling doesn't change—you still write the original third tone mark. This is purely a pronunciation shortcut. The key is to train your brain to see that "v̌ v̌" pattern and automatically make the switch before you even open your mouth.

So what happens if you get three third tones in a row? The rule just adapts to keep things smooth. For instance, wǒ hěn hǎo (我很好), meaning "I am very good", becomes wó hén hǎo (second + second + third). The goal is always to make the phrase flow better.

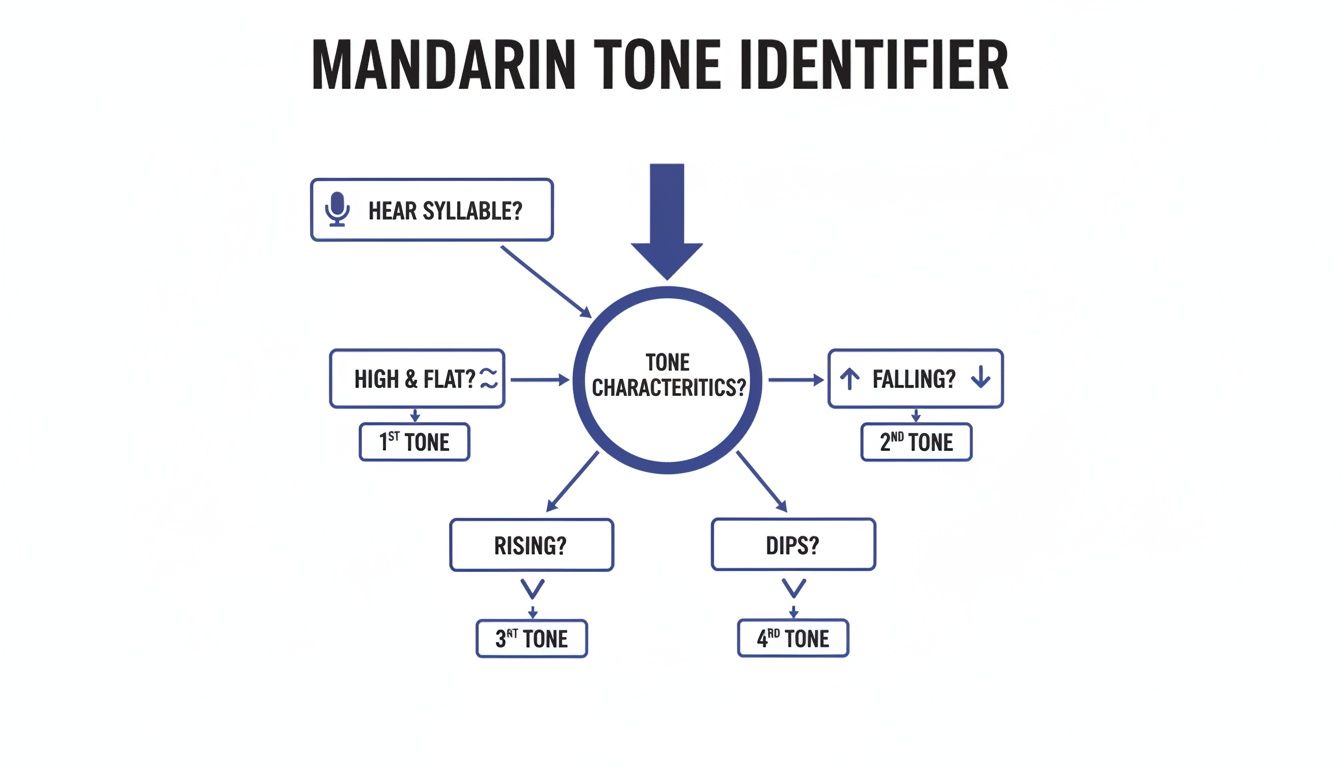

The first step is always being able to identify the basic tones as you hear them. This flowchart can help you visualise that process, which you need to master before you can start applying sandhi rules.

This decision tree shows how the pitch contour of a syllable determines its tone—a vital skill for knowing when tone sandhi rules need to kick in.

The Shifting Tones of 'Bù' and 'Yī'

Two of the most common characters in the language, 不 (bù) and 一 (yī), are total tonal chameleons. Their tones change depending on what follows them.

Tone Changes for 不 (bù)

The character 不 (bù), meaning "not," is originally a fourth tone. But it has one key exception you need to know:

- When bù is followed by another fourth tone, it changes to a second tone.

Think of it as softening the landing. Two sharp, falling tones in a row can sound a bit blunt and are clunky to say quickly.

- bù shì (不是) - "is not" becomes bú shì.

- bù qù (不去) - "not going" becomes bú qù.

In every other situation, it stays as a fourth tone. For example, bù hǎo (不好) and bù máng (不忙) keep their original tones.

Tone Changes for 一 (yī)

The character 一 (yī), meaning "one," is even more of a shape-shifter. It starts as a first tone, but you'll rarely hear it that way inside a longer word.

When yī comes before a first, second, or third tone, it switches to a fourth tone.

- yì tiān (一天) - one day

- yì nián (一年) - one year

- yì qǐ (一起) - together

When yī comes before a fourth tone, it changes to a second tone.

- yí gè (一个) - one (the most common measure word)

- yí dìng (一定) - definitely

It only keeps its original high-and-flat first tone when it's said by itself, used as an ordinal number (like "number one"), or comes at the end of a word.

These tone changes aren't just linguistic trivia; they're the glue that holds the natural flow and rhythm of the language together. Understanding them means appreciating the broader musicality of Mandarin, or what linguists call prosody in speech. Making these sandhi rules a part of your daily practice is essential. Using methods like sentence mining, which you can learn all about in our guide to comprehensible input for Chinese, is a fantastic way to internalise these patterns naturally by hearing them in context again and again.

The Fifth Tone and Other Mandarin Nuances

Just when you think you've got the four tones sorted, Mandarin throws you a curveball. But don't worry, this one's actually easier than it sounds. It's the neutral tone (轻声 qīng shēng), and it’s less of a "tone" and more of a lack of one.

Think of it like the unstressed syllables in English. Take a word like "banana." You don't pronounce each "a" with the same emphasis, do you? That middle "a" is light and quick. That's exactly how the neutral tone works in Chinese. It’s a short, unstressed syllable that has lost its original tone, creating a much more natural, rhythmic flow in everyday speech.

The pitch of a neutral tone syllable isn't fixed; it actually gets its cue from the syllable right before it. It’s like it borrows its pitch, but it’s always pronounced softly and quickly.

Hearing the Neutral Tone in Action

Chances are you've already heard the neutral tone without even realising it. It pops up all the time in common words, especially for family members or those little particles that finish off sentences.

Here’s a quick rundown of how its pitch changes depending on what comes before it:

- After a 1st tone (high): The neutral tone drops to a mid-falling pitch. A classic example is māma (妈妈) – mother.

- After a 2nd tone (rising): The neutral tone sits at a mid-level pitch. Think of yéye (爷爷) – paternal grandfather.

- After a 3rd tone (dipping): The neutral tone jumps up to a high pitch. You'll hear this in nǎinai (奶奶) – paternal grandmother.

- After a 4th tone (falling): The neutral tone becomes low-falling. A perfect example is bàba (爸爸) – father.

The real secret here isn't to memorise these pitch rules. Instead, focus on what defines the neutral tone: its lack of stress. Just learn to hear and say it as a light, relaxed sound. It’s what helps smooth out the language and make it flow.

A Quick Word on Regional Variations

Just as you can tell a Londoner from a Liverpudlian by their accent, tones in Chinese aren't uniform across the whole of China. The "standard" Mandarin you're learning, Putonghua (普通话), is based on the Beijing dialect. But the moment you step outside the classroom, you'll hear all sorts of interesting nuances.

For instance, you might notice that speakers from the south of China don't always distinguish their tones as sharply as speakers from the north. Someone from Taiwan might speak with a softer, more melodic rhythm. These aren’t mistakes—they're just regional accents, each with its own flavour.

Knowing this from the get-go is a huge advantage for your listening skills. It prepares you for the reality of conversations with real people, where pronunciation isn't always textbook-perfect.

So, if you hear a tone that sounds a bit different from what your teacher taught you, don't panic. Recognising these variations will save you a lot of confusion and turn you into a more flexible, real-world listener. It’s a key step in moving from a learner to a confident communicator who can handle the rich diversity of spoken Chinese.

Building Your Tonal Muscle Memory

Knowing the theory behind Mandarin tones is one thing, but getting your mouth to produce the right sounds without thinking? That's a whole different ball game. This is where practice turns abstract knowledge into an automatic, physical skill. We’re going to build your tonal muscle memory with a proper workout plan for your pronunciation.

Don't worry, this isn’t about mind-numbing repetition. It's about smart, targeted drills that train your ear to catch subtle differences and your voice to copy them accurately. Think of it like lifting weights at the gym; these exercises build the neural pathways you need for fluid, natural-sounding Mandarin.

Start with Minimal Pair Drills

The quickest way to sharpen your ear is by drilling minimal pairs. These are words that are identical except for the tone, like the classic mā, má, mǎ, mà set. Working with these pairs forces your brain to stop guessing from context and to focus purely on the pitch to figure out the meaning.

It’s an absolutely essential first step. Practising these regularly helps you internalise the unique musical shape of each tone, making them far easier to both recognise and produce.

Here are a few common minimal pairs to get you started:

- mǎi (买) vs. mài (卖) – to buy vs. to sell

- wèn (问) vs. wěn (吻) – to ask vs. to kiss

- tāng (汤) vs. tǎng (躺) – soup vs. to lie down

- shì (是) vs. shí (十) – to be vs. ten

Try listening to a native speaker say each pair, then have a go at mimicking them. Record yourself and compare it to the original audio. This feedback loop is your best friend for catching mistakes and fixing them.

The goal of minimal pair drills is to make the difference between tones as obvious as the difference between the letters 'b' and 'p'. It’s about training your ear until the distinction is unmistakable.

Move to Multi-Syllable Phrases

Once single syllables feel more comfortable, it's time to level up. Tones rarely live in isolation; they’re almost always part of two or three-syllable words and phrases. This is where your knowledge of tone sandhi rules gets put to the test in a real-world context.

Practising tone combinations is crucial because it mirrors the natural flow of speech. You’ll get used to the rhythm and the way pitches shift and flow into one another, which is a massive step towards sounding less like a textbook and more like a native speaker. We've got a great resource full of common phrases in Chinese that are perfect for this kind of practice.

The recent surge in Mandarin learning highlights this challenge. A rapid growth in student numbers means thousands of learners now need daily, audio-rich practice to master Mandarin tones—something that's tough to get from classroom time alone.

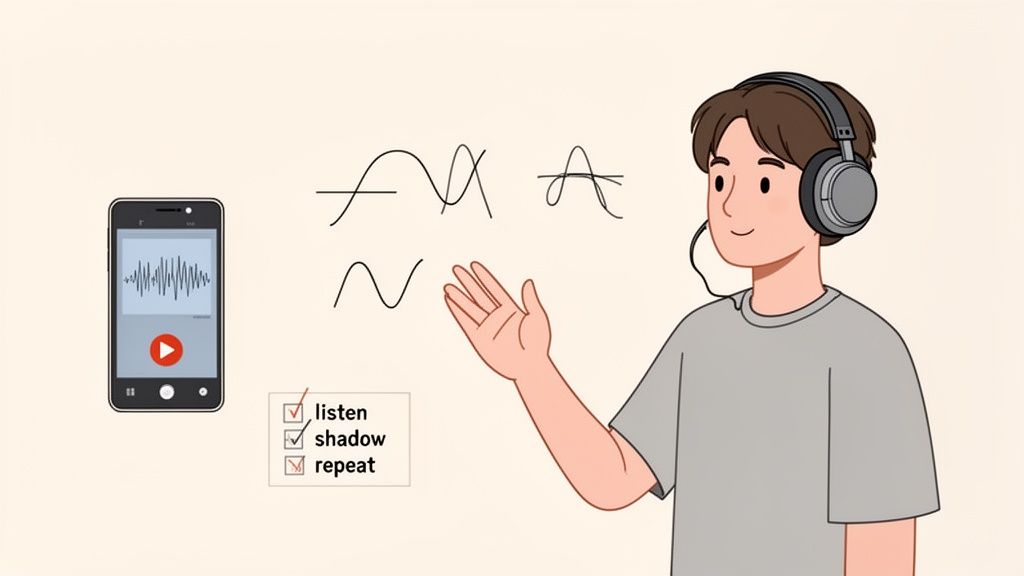

Use Listening and Shadowing Exercises

One of the most powerful techniques for building that muscle memory is shadowing. This is where you listen to native speaker audio and try to speak along with them in real time, doing your best to mimic their pronunciation, rhythm, and tones.

Shadowing is brilliant because it does two things at once: it sharpens your listening skills to pick up on the nuances of natural speech, and it trains your mouth to produce those sounds automatically. It basically creates a direct link between your ears and your voice.

Here's a simple routine to get you going:

- Listen First: Play a short audio clip (just a single sentence) from a native speaker. Don't speak, just listen carefully.

- Shadow: Play the same clip again, but this time, speak along with the recording. Forget about perfection for now; just try to match the speaker’s timing and pitch.

- Record and Compare: Now, record yourself saying the sentence on its own. Compare your version to the original native audio. Listen for any differences in your tones and try again.

For an app like Mandarin Mosaic, this kind of systematic exposure is at the core of its design. The app’s sentence-based approach means you hear new words in context, complete with lifelike audio, making it the perfect tool for the listening and shadowing drills that turn theory into an automatic skill.

Your Weekly Tone Workout

To make sure you're covering all your bases, it helps to have a structured plan. A little bit of focused practice each day goes a long way. Think of it as a weekly workout schedule for your mouth.

Here’s a sample schedule you can adapt. The idea is to keep your practice varied and consistent, preventing boredom while systematically building your skills.

Weekly Tone Practice Schedule

| Day | Focus Area | Example Exercise | Recommended Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | First Tone (High-Level) | Drill words like bā, dā, gā. Record and compare. | Audio flashcards, Anki |

| Tuesday | Second Tone (Rising) | Practise minimal pairs: mái vs. mǎi. | Mandarin Mosaic clips |

| Wednesday | Third Tone (Dipping) | Focus on third tone sandhi (e.g., nǐ hǎo). | Native speaker audio |

| Thursday | Fourth Tone (Falling) | Shadow short sentences with lots of fourth tones. | YouTube, podcasts |

| Friday | Tone Combination Drill | Practise two-syllable words (1-4, 2-3, etc.). | Mandarin Mosaic app |

| Saturday | Neutral Tone Practice | Listen for neutral tones in longer sentences. | Chinese dramas, music |

| Sunday | Review & Consolidate | Review the week’s trickiest words and phrases. | Your own recordings |

This kind of routine ensures you're not just randomly repeating sounds but are actively strengthening specific areas. Over time, you'll find the tones start to feel less like a conscious effort and more like second nature.

Avoiding Common Tonal Pitfalls

Let's be honest: every single person learning Mandarin stumbles with tones. It’s a rite of passage. But knowing where the common traps are can help you sidestep them and build good habits from the very beginning.

Most of these little mistakes come from instincts carried over from your native language. The good news? With a bit of awareness, they are completely fixable. The goal isn't instant perfection, but building a solid process of self-correction. Recognising these pitfalls is the first step to developing a more natural and accurate pronunciation of the tones in Chinese.

Forgetting to Detach from English Intonation

One of the biggest hurdles for English speakers is switching off our natural intonation patterns. We instinctively raise our pitch at the end of a question and let it fall for a statement. In Mandarin, that just doesn't work. The sentence's melody comes from the individual tones of each word, not some overarching curve.

Slapping English question intonation onto a Mandarin sentence will completely butcher the tones and leave native speakers confused. The fix is to zoom in. Focus on nailing each syllable's tone correctly, and let the sentence's "melody" build itself from that sequence.

Key Takeaway: Think of each syllable as a separate musical note. The sentence's overall sound is just a string of these notes played correctly, not an English-style melody laid on top.

The Under-Pronounced Third Tone

Ah, the third tone—the dipping tone. It's often the trickiest of the bunch. In its full form, it needs to go down and then swing back up. Learners often chop the "up" part short or just flatten the whole thing into a low, mumbled sound. This makes it almost impossible to tell apart from other tones.

A brilliant way to fix this is to get physical. Use your hand to trace a dipping "V" shape in the air as you say a third-tone word like hǎo (好). This physical motion helps build muscle memory and reminds you to complete the full contour of the sound. Exaggerate it at first! The more you practise the full dip-and-rise, the more natural it will feel.

Ignoring Tone Sandhi in Fast Speech

You might have the tone sandhi rules memorised perfectly, but applying them in the heat of a real conversation is a different beast entirely. As learners start speaking faster, it's common to revert to pronouncing each tone individually, forgetting that two third tones in a row (like in nǐ hǎo) have to change.

To combat this, you need to drill common tone sandhi pairs until the change becomes second nature.

- Practise common phrases: Repeat phrases like hěn hǎo (很好) and kě yǐ (可以) over and over. You want the second-third tone pronunciation to feel more natural than the original third-third.

- Shadow native speakers: Find short audio clips and mimic the speaker's flow exactly. This trains your ear to catch the sandhi changes and your mouth to produce them without even thinking.

This willingness to tackle tricky aspects like tones is on the rise. With a growing interest in Mandarin, mastering tones in Chinese is increasingly seen as a vital communication skill for learners.

A Few Common Questions About Mandarin Tones

To wrap things up, let's tackle some of the questions I hear all the time from learners. Getting your head around these practical points can make a real difference, building both your understanding and your confidence as you get to grips with tones in Chinese.

How Long Does It Really Take to Get Good at Tones?

There's no magic number here; it all comes down to practice and exposure. That said, most learners find they can produce individual tones pretty accurately within a few weeks of consistent work. Getting to the point where tones feel natural and automatic in conversation? That's a longer road, usually taking several months to a year.

The real key is daily, focused practice. Seriously, even just 10-15 minutes a day builds that crucial muscle memory way more effectively than a long cramming session once a week.

Can People Still Understand Me If My Tones Are Wrong?

Sometimes, but you'd be taking a massive gamble. If the context is crystal clear, a native speaker might be able to figure out what you're trying to say. For instance, if you're in a restaurant pointing right at a fish and you mess up the tone for yú, they'll probably get it.

In most other situations, though, wrong tones just lead to total confusion. A misplaced tone doesn't just sound a bit off—it changes the entire meaning of the word. Relying on context to save you isn't a solid strategy. Nailing your tones is always your best bet for being understood clearly. For language tutors, applying the best practices for online teaching can be a game-changer when explaining subtle but critical concepts like this.

Think of it this way: a tonal mistake isn't like having a slight accent. It's more like a spelling mistake that creates a completely different word. A classic mix-up is mǎi (to buy) and mài (to sell). Getting those wrong could make for a very strange shopping trip.

Are Tones the Hardest Part of Learning Mandarin?

For a lot of beginners, tones are definitely the most alien concept. But what many people discover is that once the idea "clicks," mastering tones is more about building muscle memory than a huge intellectual challenge.

Honestly, in the long run, most learners find that memorising thousands of Chinese characters is the bigger, more sustained mountain to climb. Tones are what I'd call a front-loaded difficulty. Tackle them head-on with consistent practice early, and they’ll eventually become second nature.

Do I Have to Memorise the Tone for Every Single Character?

Yep, you absolutely do. The tone is a fundamental part of a word's identity, just as vital as its consonants and vowels.

When you learn a new character or word, you should always learn its Pinyin and its tone together as one complete package. Try not to think of it as learning a word and then memorising its tone; the tone is an essential piece of the word itself.

Ready to turn all this theory into an automatic skill? The Mandarin Mosaic app is built around sentence mining, which gets you hearing and practising tones in real, natural sentences right from day one. It's time to stop drilling isolated sounds and start building true tonal intuition. Download Mandarin Mosaic and make your daily practice truly count.