Master the tone in chinese: A clear, practical guide to tones and sandhi

Getting the tone in Chinese right is probably the single most important skill you can learn for clear communication. While we use pitch to add emotional flavour to our words, in Mandarin, the pitch of a syllable completely changes what it means. Nail this from day one, and you're on the fast track to actually being understood.

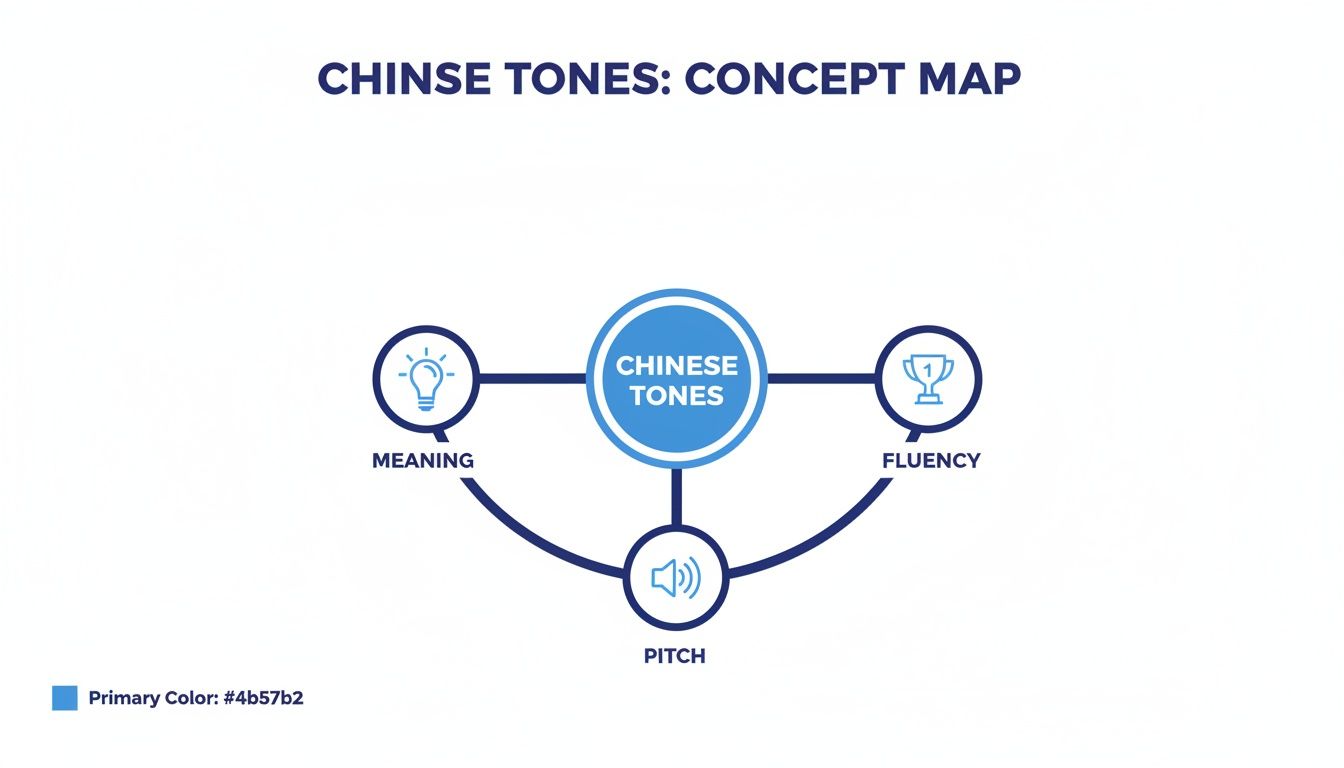

Why Chinese Tones Are Your Key to Fluency

If you've ever felt a bit intimidated by Mandarin tones, it’s time for a fresh perspective. They aren't some random hurdle designed to trip you up; they're the predictable, logical system that holds the entire language together. Without them, communication just falls apart.

Think about it – you already use pitch changes in your own speech. When you ask a question like, "You're going to the shop?", your voice naturally lifts at the end. When you're excited, your pitch shoots up. This is called intonation, and it's all about emotion. A tone in Chinese takes that idea one step further by defining the word's actual meaning.

The Foundation of Meaning

In a tonal language like Mandarin, the exact same syllable can mean completely different things depending on its pitch contour. This isn't a tiny detail; it's the difference between ordering your lunch and accidentally saying something deeply embarrassing.

Take the classic example of the syllable "ma":

- mā (妈), with a high, flat tone, means mother.

- má (麻), with a rising tone, means hemp.

- mǎ (马), with a dipping-then-rising tone, means horse.

- mà (骂), with a sharp, falling tone, means to scold.

You can see how mixing these up could lead to some very strange conversations. Getting tones right isn't about chasing a perfect accent; it’s about making sure your message lands clearly. You can learn more about how these small details make a huge impact in our guide on effective communication with language.

The crucial takeaway is this: tones aren't optional. They are as fundamental to a Chinese word as vowels and consonants are. Ignoring them is like trying to speak without using any vowels.

This guide will break down the four main tones plus the gentle neutral tone, showing you that with the right approach, they are entirely manageable. By shifting your mindset from fear to confidence, you can start seeing tones not as an obstacle, but as your most powerful tool for fluency.

Decoding the Four Main Tones and the Neutral Tone

Alright, let's get to the heart of what makes Mandarin sound like, well, Mandarin. The four main tones are the absolute bedrock of pronunciation. Each one has a distinct pitch contour that completely changes a word's meaning. Think of them as musical instructions for your voice that you attach to each syllable.

Getting a feel for the unique "shape" of each tone in Chinese is your first massive step toward speaking clearly. We'll break them down one by one, using some simple analogies to help the feeling stick.

The Four Pillars of Mandarin Pronunciation

Each of the four tones has a specific movement. If you can visualise and feel this movement in your own voice, you'll be miles ahead of someone just trying to memorise numbers.

Here’s a practical look at them:

First Tone (mā, 妈): This is the high, flat tone. Picture a doctor asking you to open up and say "ahhh". Your voice stays high and level, with no wobbles. It’s like holding a single, sustained high note.

Second Tone (má, 麻): This is the rising tone. It has that same upward lilt you’d naturally use when asking a question like, "What?". Your voice starts around your mid-range and shoots up smoothly and quickly, as if you're genuinely curious about something.

Third Tone (mǎ, 马): The dipping tone is often the one that trips learners up the most. It starts in the middle, drops down low, and then rises back up. Think of the sound you might make when you're a bit hesitant or surprised, like, "Oh... really?".

Fourth Tone (mà, 骂): This is the falling tone. It's sharp, quick, and decisive. Imagine you're giving a firm, sudden command like "Stop!" or "Go!". Your voice starts high and drops straight down.

To help you see how these tones fit together, here’s a quick summary table.

The Four Main Tones of Mandarin at a Glance

| Tone Number | Pinyin Mark | Pitch Contour | Description and Analogy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mā (¯) | High & Flat | A sustained, high note, like a doctor’s “ahhh.” |

| 2 | má (´) | Mid to High (Rising) | A question’s upward lilt, like asking, “What?” |

| 3 | mǎ (ˇ) | Mid-Low-Mid (Dipping) | A hesitant dip and rise, like saying, “Oh… really?” |

| 4 | mà (`) | High to Low (Falling) | A sharp, decisive drop, like shouting, “Stop!” |

Learning these isn't just a technical drill; it's about connecting the sounds you make directly to the meaning you want to convey.

This concept map shows just how central tones are to linking pitch with meaning and, ultimately, fluency.

As you can see, getting tones right isn't just an optional extra. It's the bridge that connects correct pronunciation to real comprehension and speaking with confidence.

The Fifth Tone: The Neutral One

Alongside the main four, you'll also come across the neutral tone, sometimes called the fifth tone. This one is a bit different because it doesn't have its own fixed pitch contour. Instead, it’s short, light, and unstressed—almost like an afterthought tagged onto the end of a word.

The neutral tone gets its pitch from the tone of the syllable that comes just before it. It’s like a little linguistic piggyback ride, making the language flow more smoothly.

You'll spot it frequently on the second syllable of two-syllable words, like in "bàba" (爸爸, father), or on grammatical particles like "ma" (吗) which turns a statement into a question. The key is to keep it quick and soft. For more on how tones are shown in writing, have a look at our guide on how to learn Chinese Pinyin.

The value of structured tone training is clear when you look at successful initiatives like the UK's Mandarin Excellence Programme, which has expanded to 80 partner schools across England. Starting with fewer than 400 participants before 2016, the programme now involves over 16,000 students—blowing past its original 2020 target of 5,000. This focus has helped GCSE entries for Chinese leap from just over 3,000 to more than 7,800 in recent years. You can read the full research on these language trends from the British Council.

Just when you think you’ve got a handle on the four tones, you start noticing something odd in real conversations: the tones don't always sound the way they look on paper. This isn't a mistake; it's a core feature of spoken Mandarin called tone sandhi. These are predictable rules that help the language flow more smoothly, ironing out clunky or difficult-to-say tone combinations.

Think of tone sandhi as a kind of linguistic politeness, where one tone adjusts itself to make its neighbour sound better. These changes aren’t random at all—they follow very clear patterns. Getting your head around them is non-negotiable if you want to understand native speakers and make your own speech sound natural.

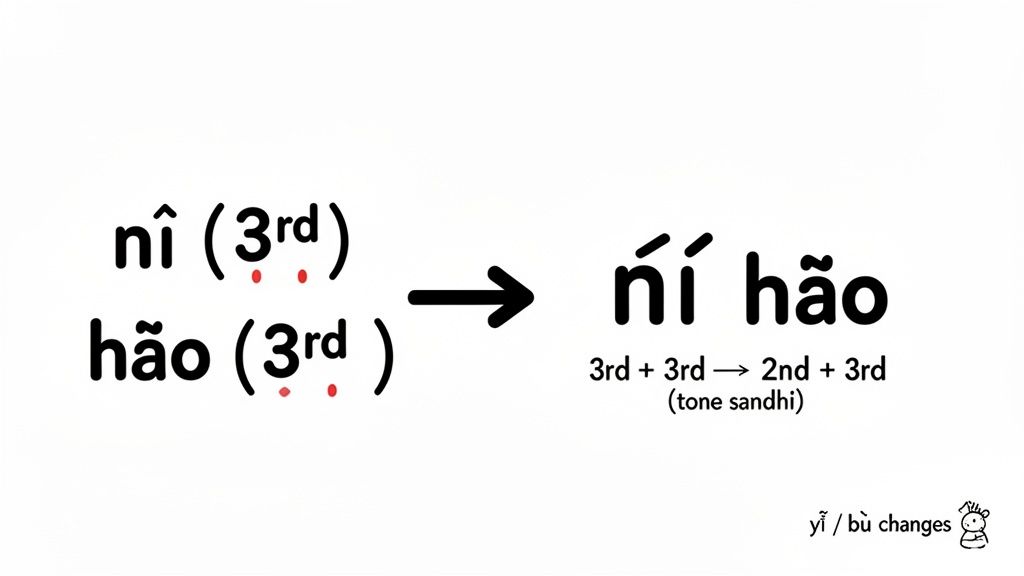

The Most Common Rule: Two Third Tones

The most important tone sandhi rule you'll run into, time and time again, involves two third tones sitting next to each other. That dipping third tone is already a bit of a workout for your vocal cords, and saying two in a row is physically awkward and slows you right down. Luckily, the language has a simple, elegant fix.

When two third-tone syllables appear together, the first one automatically changes to a rising second tone. The most famous example is the greeting nǐ hǎo (你好).

- On their own, both nǐ (你) and hǎo (好) are third tones.

- But say them together, and nǐ shifts to a second tone: ní hǎo.

- Crucially, this change only happens in speech. The pinyin mark (ˇ) stays the same when you write it.

This rule is rock-solid and applies to countless common phrases, like kěyǐ (可以), meaning "can," which is pronounced kéyǐ. Mastering this one tweak will give your listening comprehension and spoken fluency an immediate, noticeable boost.

The two-third-tones rule is non-negotiable in spoken Mandarin. It’s not a stylistic choice but a fundamental feature that makes the language easier to speak. Hearing it and using it correctly is a key signpost on your path to fluency.

Other Essential Sandhi Rules

Beyond the third tone puzzle, two other characters have their own special chameleon-like rules: yī (一), for "one," and bù (不), for "not." How they’re pronounced depends entirely on the tone of the syllable that comes right after them.

Here’s how they work:

The Tone of Yī (一):

- When it comes before a fourth tone, yī changes to a second tone. For instance, yīgè (一个), a common measure word, is pronounced yígè.

- When it comes before a first, second, or third tone, yī changes to a fourth tone. A great example is yìtiān (一天), meaning "one day."

The Tone of Bù (不):

- Normally, bù is a fourth tone. But when it’s immediately followed by another fourth tone, it softens into a second tone. For example, bùshì (不是), meaning "is not," is pronounced búshì.

These sandhi rules might feel like a lot to memorise at first, but with enough listening and speaking practice, they become second nature. They are the invisible threads that weave individual syllables into the smooth, melodic rhythm of authentic spoken Chinese.

Right, so you’ve got the theory of Chinese tones down. But stringing them together correctly in a real conversation? That's a whole different ball game. It’s incredibly common for learners to fall into the same predictable traps, leading to mix-ups that can be anything from slightly confusing to genuinely embarrassing. The first step to fixing these bad habits is knowing what they are.

One of the biggest hurdles is getting the second and third tones mixed up. They both have a rising pitch at some point, so it’s easy to see why. Learners often can’t quite nail the difference between the quick, smooth rise of the second tone and the drawn-out, dipped rise of the third. This is a dangerous one because it can completely change what you’re trying to say.

For instance, asking someone a wèn tí (问题), which uses the fourth and second tones for "question," is a world away from saying wěn tí. That combination doesn’t have a common meaning, but it involves the third tone "wěn" (吻), which means "to kiss." You can see how that might get awkward.

The Lazy Third Tone Trap

Another classic mistake is the "lazy" third tone. The full third tone is a dip followed by a rise, and honestly, it takes a bit of vocal effort. To save energy, loads of learners just do the initial dip and chop off the final rise. Now, this "half-third tone" is a real thing in Mandarin when it comes before another tone, but if you use it at the end of a sentence, your speech just sounds flat and unnatural.

To fix this, get into the habit of really exaggerating the full V-shape of the third tone on standalone words. Picture your voice tracing a valley – you have to go all the way down before you can come back up.

Letting Your Native Intonation Interfere

Finally, if you speak a non-tonal language, your brain is wired to use intonation to show emotion or ask questions. It’s a subconscious habit. You might raise your pitch at the end of a sentence to ask a question, accidentally turning a fourth tone into a second tone and wrecking all your hard work.

The trick is to actively separate your feelings from your pitch. In Mandarin, the meaning is baked into the tone of each word, not the overall melody of the sentence. Your job is to focus on hitting each syllable's tone accurately, almost like playing notes in a song.

Here are a couple of high-stakes minimal pairs that show just how critical getting your tones right is:

- mǎi (买) vs. mài (卖): Are you trying to buy (third tone) something, or to sell (fourth tone) it? One little slip of the tone and you’ve completely reversed the deal.

- shuìjiào (睡觉) vs. shuǐjiǎo (水饺): Are you telling someone you want to sleep (fourth tone), or that you’re craving dumplings (third tone)? This is a classic learner mistake and pretty much a rite of passage.

By zoning in on these specific errors, you can start turning that theoretical knowledge into practical, accurate speech. It's all about building the right muscle memory. That’s what separates learners who just get by from those who speak with real clarity and confidence.

How to Practice and Internalize Chinese Tones

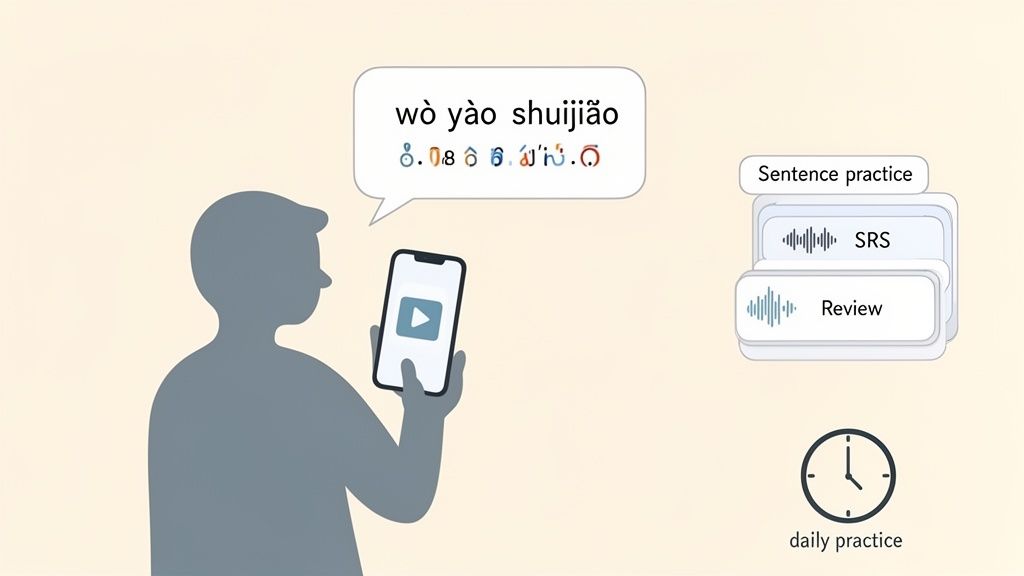

Knowing the rules of Mandarin tones is one thing, but getting them to roll off your tongue naturally is a completely different beast. The classic approach of drilling tones from isolated word lists is often a dead end. Why? Because it strips away the natural rhythm and flow of the language. Real mastery comes from context.

To bridge the gap from knowing the tones to using them, you need a smarter practice strategy. The single most effective way to internalize tones is to learn them within complete sentences. This method helps your brain absorb not just the individual pitch of a word, but the musicality of how tones dance together in real speech.

This is precisely why a sentence-focused approach is so powerful. When you listen to and mimic full sentences, you’re training your brain to connect a word, its tone, and its proper usage all at once. It creates a memory link that's far stronger and more durable than studying vocabulary in a vacuum.

Sentence Mining and Contextual Learning

A technique called sentence mining is the perfect way to put this into practice. Instead of grinding through flashcards with single words, you focus on sentences that are just one tiny step beyond what you already know. It allows you to see a new word and its tone in a meaningful context right away.

This is where a specialised tool can make a world of difference. Mandarin Mosaic, for example, is built around this exact principle. It organises your learning through sentences that introduce one new word at a time, letting you see vocabulary in action from day one. You can find out more about optimising your study sessions with our guide on the best memory flash card techniques.

The goal of contextual practice isn't just to know the tone, but to feel it as part of a word's identity. This transforms tone practice from a robotic drill into a natural process of language acquisition.

Using Technology to Your Advantage

Modern apps provide the ideal environment for this kind of contextual practice. A good tool should offer features that reinforce correct tone production without derailing your study flow.

Here’s what to look for in a practice tool:

- Sentence-Focused SRS: A Spaced Repetition System that uses sentences, not just words, ensures you review tones in context at the perfect moment for long-term memory.

- Clear Native Audio: Instantly hearing how a native speaker pronounces a sentence is non-negotiable. The ability to listen and repeat trains both your ear and your mouth.

- Integrated Dictionary: A one-tap dictionary lets you check a word’s meaning and tone without having to switch apps and lose your focus.

The success of structured language programmes in the UK really highlights how vital consistent practice is. The first group of students from the Mandarin Excellence Programme achieved GCSE results that were on par with those from elite independent schools. It’s solid proof that state school students can absolutely master Mandarin's four tones with enough weekly hours.

But a significant gap remains. Even though only 7% of English children attend independent schools, they made up 33% of all Chinese GCSE entries in 2019—a disparity the British Council has called 'particularly dramatic'. This just underscores how crucial it is to have accessible and effective learning tools for every single student.

As you practice and internalise Chinese tones, you're always aiming for accuracy in your pitch. Digging into concepts like tone match can offer some interesting insights into how vocal qualities are analysed, which is directly relevant to hitting those tones just right. By combining sentence-based learning with powerful tools, you can finally move beyond theory and start speaking with real confidence.

As you get deeper into Mandarin, a few questions about tones almost always bubble up. It's only natural to wonder about the practical side of things, like how much mistakes really matter or what the journey to getting them right actually looks like. Let's cut through the noise and tackle these common queries head-on.

This will help you set realistic expectations and keep you moving forward with confidence.

Can People Understand Me if My Tones Are Wrong?

This is the big one. While context can sometimes save you from a minor slip-up, getting tones wrong consistently leads to serious confusion. It’s not just about sounding a bit off; wrong tones can completely change the meaning of your words, often with hilarious or awkward results.

The classic example is mixing up shuìjiào (睡觉, to sleep) and shuǐjiǎo (水饺, dumplings). Telling a restaurant owner "wǒ yào shuìjiào" (I want to sleep) instead of "wǒ yào shuǐjiǎo" (I want dumplings) will, at best, get you a very confused look. Accurate tones aren't a bonus feature for advanced learners; they are essential for clear communication right from day one.

How Long Does It Really Take to Master Tones?

There's no magic number here, but it helps to think about it in stages. You can probably learn to recognise the four main tones within a few weeks of focused practice. Being able to produce them correctly on single words might take a few months.

However, nailing tones perfectly in fluent, spontaneous conversation is a long-term goal. It’s a lot like learning a musical instrument; your skill improves with consistent, daily practice, not by cramming. The key is hearing and using tones in full sentences, not just drilling isolated words.

Think of tone mastery not as a finish line you cross, but as a path you walk. Every day of practice smooths the way, making your speech more natural and your listening sharper.

This whole journey is about gradual improvement, not overnight perfection.

Do Native Speakers Ever Make Tone Mistakes?

This is a common question, and the answer is a bit nuanced. Native speakers don't "get tones wrong" in the way a learner does, like mixing up a second tone for a third. What you might be hearing are natural variations based on regional accents, how fast they're talking, or emotional emphasis.

Often, what sounds like a mistake to a learner is actually the correct application of more advanced rules, such as:

- Tone sandhi: Those predictable tone changes we covered earlier, which are completely automatic for native speakers.

- Neutral tone: The light, unstressed syllables that make speech flow much more naturally.

These aren't errors. They're the hallmarks of fluent, authentic speech that you'll gradually absorb over time.

Should I Learn Tones with Marks or Numbers?

For effective, long-term learning, you should absolutely focus on the pinyin marks (also called diacritics). These visual cues—the flat line (¯), rising tick (´), V-shape (ˇ), and falling tick (`)—directly show you the pitch contour of the tone in Chinese.

- Pinyin Marks: They are visually intuitive and help you build a strong mental picture of how each tone should sound. This creates a direct link between the written word and its correct pronunciation.

- Numbers: While numbers (1, 2, 3, 4) are much easier for typing on a keyboard, they don't give you the same immediate visual feedback. They're an abstract layer, forcing you to do an extra mental conversion step.

Using the marks from the get-go helps you internalise the "shape" of each tone, making your recall faster and more accurate in the long run.

Ready to stop memorising tones and start internalising them in context? Mandarin Mosaic is designed around sentence-based learning, helping you master vocabulary and tones naturally. See how our sentence-focused SRS and clear native audio can transform your practice.