A Practical Guide to Mastering Sentences in Chinese

Learning how to build sentences in Chinese can feel like a huge mountain to climb, but the basic structure is surprisingly logical. In fact, at its core, Chinese follows a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) word order – exactly the same as English. This simple, reliable blueprint is your starting point, and it makes the initial learning curve much gentler than most people expect.

The Blueprint for Building Sentences in Chinese

Staring at a string of Chinese characters can feel like trying to solve a puzzle without the picture on the box. But what if I told you the core blueprint is one you already know? The foundational logic of Mandarin sentences rests on a pattern that's second nature to English speakers.

This structure is the very bedrock of communication in Chinese. Unlike languages that get bogged down in complex verb conjugations to show tense, Mandarin keeps the word order fixed and simply adds particles to convey extra meaning. It's a system that makes constructing your first sentences refreshingly straightforward.

The Power of SVO Structure

The Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) pattern is your most reliable friend in Chinese. It works just as you'd expect, which is a massive head start.

- Subject: The person or thing doing the action.

- Verb: The action itself.

- Object: The person or thing on the receiving end of the action.

Let's take one of the most common phrases: "I love you." In Chinese, the pieces slot into place in the exact same order. You can almost translate it word-for-word.

我爱你 (Wǒ ài nǐ)

- 我 (Wǒ) = I (Subject)

- 爱 (ài) = love (Verb)

- 你 (nǐ) = you (Object)

This consistency is one of the best things about Chinese grammar. Once you get this simple sequence down, you can already form countless correct and meaningful sentences. It’s a practical first step that builds a solid framework, turning confusion into confidence from day one.

Why This Matters for UK Learners

This logical SVO structure is a big reason why Chinese has surged in popularity across the UK. It’s become one of the most useful second languages, with a huge 40% of Britons picking it over all others in a YouGov survey. As China's economy continues to grow and strengthen trade links, mastering basic Chinese sentences gives you a real edge in an increasingly globalised job market. You can read more about these language trends in the YouGov survey findings.

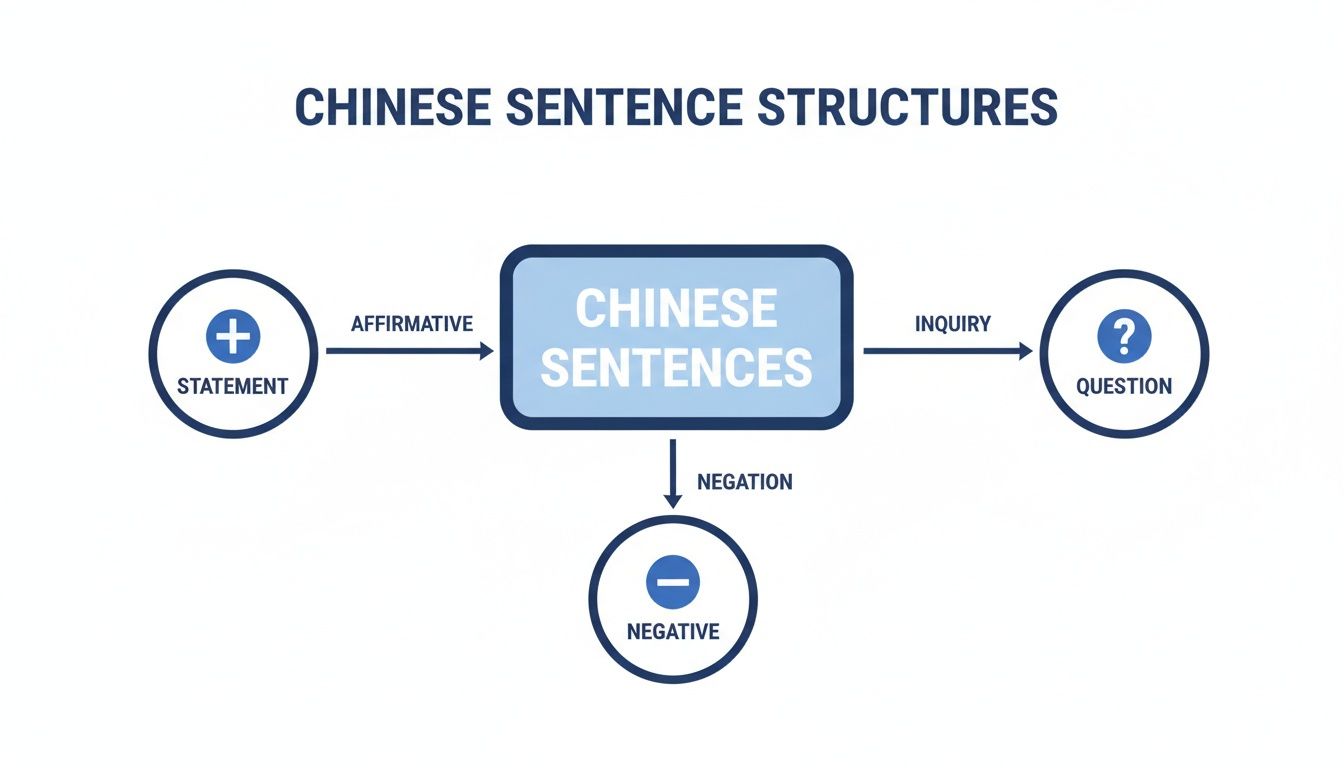

Once you've got the basic SVO blueprint down, you can start building real, practical sentences right away. The next step is to get a feel for a few essential patterns that turn this simple structure into statements, questions, and negations – the absolute bread and butter of everyday conversation.

Think of these patterns as your starter toolkit. Just like a chef gets a handle on a few basic sauces to whip up hundreds of different dishes, you can use these core structures to express a massive range of ideas. They are the workhorses of Mandarin.

Creating Simple Statements

The most direct pattern is the simple statement. It follows the Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order we’ve already looked at. This is how you’ll make observations, share what you're doing, and describe the world around you.

- Structure: Subject + Verb + Object

- Example: 我喝茶 (Wǒ hē chá) - I drink tea.

- Example: 他看书 (Tā kàn shū) - He reads a book.

Notice how the verb doesn't change for "he" versus "I." The structure stays clean and consistent, which is a massive plus when you're just starting to form your first sentences in Chinese.

Asking Questions with 吗 (ma)

Turning a statement into a simple yes-no question is ridiculously easy. You just pop the particle 吗 (ma) onto the end of a statement. That's it. You don't change the word order at all. It basically acts like a spoken question mark.

The particle '吗' (ma) is a key that instantly unlocks your ability to ask questions. Simply take a complete, affirmative sentence and add '吗' to the end. The word order of the original statement remains completely unchanged.

Let's take one of our earlier statements and flip it into a question:

- Statement: 你喝茶 (Nǐ hē chá) - You drink tea.

- Question: 你喝茶吗? (Nǐ hē chá ma?) - Do you drink tea?

This simple addition is a powerful tool for kicking off conversations and finding things out. It’s an elegant feature of the language that makes asking questions incredibly straightforward. If you want to expand your conversational toolkit, check out our guide on other essential Chinese basic phrases.

Expressing Negation with 不 (bù) and 没 (méi)

To make a sentence negative, your go-to word will usually be 不 (bù). You just place it directly before the verb to say "no" or "don't."

- Structure: Subject + 不 (bù) + Verb + Object

- Example: 我不喝茶 (Wǒ bù hē chá) - I don't drink tea.

Another crucial negative word is 没 (méi). This one is typically used to say that something didn't happen in the past, or that something doesn't exist.

- Structure: Subject + 没 (méi) + Verb + Object

- Example: 他没看书 (Tā méi kàn shū) - He didn't read the book.

Getting the hang of the difference between 不 (bù) and 没 (méi) is vital for speaking accurately. A good rule of thumb is to think of 不 (bù) for negating current habits or future plans, and 没 (méi) for negating past actions or existence.

To help you see these fundamental patterns side-by-side, here’s a quick-reference table.

Fundamental Chinese Sentence Patterns at a Glance

| Pattern Type | Structure Formula | Example Sentence (Characters) | Pinyin | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Subject + Verb + Object | 我喝茶 | Wǒ hē chá | I drink tea. |

| Question | Subject + Verb + Object + 吗? | 我喝茶吗? | Wǒ hē chá ma? | Do I drink tea? |

| Negative (Present) | Subject + 不 + Verb + Object | 我不喝茶 | Wǒ bù hē chá | I don't drink tea. |

| Negative (Past) | Subject + 没 + Verb + Object | 我没喝茶 | Wǒ méi hē chá | I didn't drink tea. |

Mastering these core patterns—statements, questions with 吗 (ma), and negations with 不 (bù) and 没 (méi)—gives you a solid foundation. With just these tools, you can already build a huge number of useful sentences for daily communication.

Adding Detail with Time, Place, and Manner

Basic Subject-Verb-Object sentences are your bread and butter, but real communication happens in the details. A common stumbling block for English speakers is figuring out where to slot in extra info like when, where, and how something happened. The rule is simple, but it’s a big one: these details always come before the verb.

Think of it like setting the stage for a play. In Chinese, you paint the backdrop first—the time and the place—before the main action (the verb) kicks off. English is pretty flexible ("I ate dumplings in Beijing yesterday"), but Chinese sentence order is much stricter on this point.

The Golden Rule of Word Order

Once you get the hang of it, the standard sequence for adding detail to your sentences in Chinese is refreshingly logical. The different parts of the sentence stack up neatly, creating a crystal-clear picture for the listener.

The formula looks like this: Subject + Time + Place + Manner + Verb + Object

Not every sentence will have all these pieces, but whenever they do show up, they have to follow this order. This structure means that by the time you reach the verb, all the context is already perfectly clear.

In Chinese grammar, context always comes first. You establish the "when," "where," and "how" of a situation before you describe the action itself. This foundational principle is key to sounding natural and being understood correctly.

Putting the Rule into Practice

Let's take a simple sentence and build it up into something more descriptive. We'll start with "I eat dumplings" and add layers of detail one by one, making sure to follow the correct word order.

- Basic Sentence: 我吃饺子。(Wǒ chī jiǎozi.) - I eat dumplings.

- Adding Time: 我 昨天 吃饺子。(Wǒ zuótiān chī jiǎozi.) - I ate dumplings yesterday.

- Adding Place: 我昨天 在北京 吃饺子。(Wǒ zuótiān zài Běijīng chī jiǎozi.) - Yesterday, in Beijing, I ate dumplings.

- Adding Manner: 我昨天在北京 高兴地 吃饺子。(Wǒ zuótiān zài Běijīng gāoxìng de chī jiǎozi.) - Yesterday, in Beijing, I happily ate dumplings.

See how each new bit of information slots in perfectly before the verb "吃" (chī)? This flowchart helps to visualise the different sentence types you'll come across.

This shows how you can modify basic statements to create questions or negative forms, which are the core structures of everyday communication.

This growing need for clear communication is reflected across the UK. The 2021 England and Wales Census showed 141,052 speakers of Chinese languages, with Mandarin frequently heard in cities like London and Manchester. For learners, this means exposure to real-world sentences is more vital than ever. Mandarin Mosaic helps by curating sentence packs from beginner dialogues to advanced chats, perfect for mastering these structures. You can learn more about the UK's linguistic landscape by exploring the language data from the census.

Getting this "set the stage first" concept down is a huge step toward fluency.

How Sentence Mining Unlocks Natural Fluency

How do you get from consciously sticking grammar rules together to actually feeling what sounds right? The secret is a powerful technique called sentence mining. Instead of memorising words in isolation, you learn them with grammar, tucked inside a complete, natural sentence.

This method flips traditional learning on its head. Forget staring at a flashcard for "昨天" (zuótiān - yesterday) and then wondering where it fits. Instead, you learn it inside a real sentence. This immediately shows you that time words come before the verb, embedding the rule in your mind without a single dry explanation.

From Rules to Intuition

Sentence mining is all about absorbing word order and nuance organically. Your brain starts to spot the patterns on its own, ditching the need to memorise abstract rules. After a while, the correct structure for sentences in Chinese simply starts to feel right, just like it does in English.

This is where a dedicated tool can make a world of difference. You could try mining sentences on your own, but an app like Mandarin Mosaic is built specifically to make this process smooth and effective. It's designed to present sentences with just one new idea at a time, creating a focused learning loop that really works.

Sentence mining is about learning grammar as a byproduct of understanding meaning. By focusing on the message of a complete sentence, you internalise the structure without getting bogged down in abstract rules. It’s a practical path to genuine fluency.

Learning Smarter with Technology

Apps built for sentence mining can seriously supercharge your learning by using proven memory techniques. Mandarin Mosaic, for example, uses a spaced repetition system (SRS). This is a clever method for scheduling reviews at the perfect moment to shift information from your short-term to your long-term memory. It makes sure you actually remember what you've learned.

This screenshot from the app shows exactly how it works. A new word is presented within a sentence, letting you learn its meaning and its proper place at the same time.

The interface highlights the new word, giving you instant access to its definition and audio without breaking your flow. This tight integration of vocabulary, context, and repetition is what makes the whole process click. If you're keen to dive deeper into the theory, you can learn more about the principles of sentence mining in our detailed guide. It’s all about learning smarter, not just harder.

Common Sentence Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Every learner hits a few bumps on the road to fluency, but spotting the common pitfalls is the quickest way to smooth them out. A lot of the mistakes English speakers make in Chinese come from one simple habit: trying to force English grammar rules where they just don't fit.

This little troubleshooting guide will walk you through the classic errors that can make your speech sound a bit off. By breaking them down, you'll sharpen your accuracy and start communicating much more clearly.

Misusing 是 (shì) with Adjectives

One of the most frequent slip-ups is using the verb 是 (shì), which means "to be," to connect a noun with an adjective. In English, we say "He is tall," so it feels completely natural to translate that word for word.

- Common Mistake: 他是高。(Tā shì gāo.)

- Correct Sentence: 他很高。(Tā hěn gāo.)

So, what's going on here? The word 很 (hěn), which you might know as "very," steps in to act as the default link between a subject and an adjective. While it can mean "very," in sentences like this, it often just functions like the English "is" or "are" to make a simple, neutral statement. Slapping 是 (shì) in there for a basic description is a grammatical no-go.

Confusing 不 (bù) and 没 (méi)

Another regular point of confusion is picking the right word for "not." Both 不 (bù) and 没 (méi) translate to "not" or "no," but you can't just swap them around—they live in different grammatical worlds.

Here’s a simple way to think about it: 不 (bù) is for negating habits, intentions, and states of being (in the present or future). 没 (méi) is for negating actions that happened in the past, or the existence of something.

Let's look at a quick comparison:

- 不 (bù) is for habits: 我不喝咖啡 (Wǒ bù hē kāfēi) means "I don't drink coffee" (as a general habit).

- 没 (méi) is for past events: 我没喝咖啡 (Wǒ méi hē kāfēi) means "I didn't drink coffee" (today, or at a specific time in the past).

Getting this right is a game-changer, as using the wrong one can completely alter what you're trying to say.

Misplacing Time and Place Words

As we've touched on, one of the biggest mental shifts from English is that context—like time and place—always comes before the action. Tacking these details onto the end of a sentence, as we do all the time in English, is a dead giveaway that you're new to the language.

- Common Mistake: 我去了商店昨天。(Wǒ qùle shāngdiàn zuótiān.)

- Correct Sentence: 我昨天去了商店。(Wǒ zuótiān qùle shāngdiàn.)

Always remember the golden rule: set the scene first (who, when, where), and then describe what happened. Getting this pattern down is a massive step toward building more natural-sounding sentences in Chinese.

Here's a quick summary of these common trip-ups to help you keep them straight.

Common Mistakes in Chinese Sentence Construction

| Common Mistake | Correct Sentence | The Rule to Remember |

|---|---|---|

| 他是高。(Tā shì gāo.) | 他很高。(Tā hěn gāo.) | Use 很 (hěn), not 是 (shì), to link a noun and an adjective in a simple description. |

| 我不去了。(Wǒ bù qùle.) | 我没去。(Wǒ méi qù.) | Use 没 (méi) to negate past actions. 不 (bù) is for present/future intentions or habits. |

| 我吃饭在餐厅。(Wǒ chīfàn zài cāntīng.) | 我在餐厅吃饭。(Wǒ zài cāntīng chīfàn.) | Place and time words come before the verb. Follow the S-T-P-V-O structure. |

Nailing these small details is crucial for sounding more fluent. It’s a lot like knowing the right way to connect your ideas. If you’re looking to get even better at that, you can learn more about how to say 'and' in Chinese in our detailed article.

Your Questions on Chinese Sentences Answered

As you start piecing together sentences in Chinese, it’s completely normal for a few questions to pop up. This section is all about clearing up some of the most common sticking points learners run into. Getting these ideas straight will really boost your confidence and help you move forward.

What Is the Biggest Difference Between English and Chinese Sentence Structure?

The single biggest shift you need to make is where you put information like time and place. In English, we’re pretty flexible. "I went to the park yesterday" sounds just as natural as "Yesterday, I went to the park."

Chinese doesn't give you that freedom. Time words must go before the verb. So, the only correct way to say it is "我昨天去了公园" (Wǒ zuótiān qùle gōngyuán). The logic of Chinese grammar is that you have to "set the scene" first by stating when and where something happened, before you say what happened. Getting this "Time-Place-Action" sequence into your head is the key to sounding natural.

A great way to remember this is to think of Chinese sentences like a story told in perfect chronological order. First, you give the context (the when and where), and only then do you get to the main event (the verb). This logical flow is a cornerstone of Mandarin grammar.

How Can I Practise Building Sentences by Myself?

Getting in some consistent solo practice is absolutely essential for making progress. A brilliant place to start is just translating simple English sentences into Chinese, paying super close attention to the SVO structure and the rules for placing time and place words. This kind of deliberate practice really helps the patterns stick.

Another fantastic technique is "shadowing." This just means listening to a native speaker say a sentence and then immediately repeating it, trying your best to copy their pronunciation, rhythm, and intonation.

You can also use a tool like Mandarin Mosaic, which gives you thousands of correct sentence examples to work with.

- Translation Practice: Write out simple English sentences and try to put them into Chinese.

- Shadowing: Listen to and repeat native audio to build up that muscle memory for sentence flow.

- Sentence Banks: Use apps with huge sentence libraries to expose yourself to correct patterns over and over again.

Mixing active construction with this kind of passive absorption is a really powerful way to sharpen your skills.

Why Is Learning Full Sentences Better Than Just Vocabulary Lists?

Learning words on their own is like having a pile of bricks but no blueprint for building a house. You might know the individual words for "I," "buy," and "apple," but that doesn't automatically mean you know how to string them together to say, "I want to buy an apple."

Learning full sentences in Chinese gives you all that crucial context. It teaches you the grammar, the word order, and how words are properly used, all at the same time.

For instance, learning the sentence "我想买一个苹果" (Wǒ xiǎng mǎi yīgè píngguǒ) does more than just teach you vocabulary. It also reinforces the standard SVO structure and introduces you to the correct measure word, "个" (gè), for apples. It's a much more efficient way to build real-world communication skills than just memorising isolated words from a list.

Is Chinese Grammar Really That Different?

In some pretty major ways, yes. Chinese grammar has a few features that can feel a lot less complicated than English grammar, which is a huge relief for most learners.

For starters, there are no verb conjugations. The verb "to go" (去, qù) stays the same whether it's "I go," "he goes," or "they go." On top of that, Chinese has no noun genders or fiddly plural forms, which cuts out a massive amount of memorisation.

But the complexity is just in different places. The real challenge in Chinese grammar comes from mastering its rigid word order, using the correct measure words for different nouns, and getting your head around aspect particles, which show the state of an action. So, it's not that the grammar is necessarily "easier"—it's just different. Its structure is very logical and consistent, which makes it very learnable, especially if you focus on the patterns right from the start.

Ready to move beyond rules and start absorbing sentence structures naturally? Mandarin Mosaic is designed to make sentence mining simple and effective. It provides thousands of sentences that introduce new concepts one at a time, helping you build a strong, intuitive sense of grammar. Download the app and start building better sentences today by visiting https://mandarinmosaic.com.