Your Ultimate Guide to Numbers in Chinese Mandarin

Learning numbers in Mandarin is surprisingly logical. It's not about memorising hundreds of unique words; instead, the whole system is built on just ten core symbols. Once you get your head around the numbers from one to ten, you can combine them like building blocks to form almost any other number you can think of.

Mastering the Core Numbers From 0 to 10

Everything in the Chinese numbering system starts right here. Think of these first ten numbers as the alphabet for counting. Every larger number, from eleven to a hundred million, is built using these fundamental characters. Nailing them down—including their pronunciation and tones—is the single most important first step you can take.

To get you started, let's lay out these essential building blocks in a quick reference table. Pay close attention to the Pinyin and the tone marks above the letters, as they’re absolutely vital for getting the pronunciation right. If you need a refresher on the sound system, our guide on how to learn Chinese Pinyin is a great place to start.

The Foundational Mandarin Numbers 0 to 10

| Numeral | Chinese Character (Hanzi) | Pinyin (with Tone) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 零 | líng |

| 1 | 一 | yī |

| 2 | 二 | èr |

| 3 | 三 | sān |

| 4 | 四 | sì |

| 5 | 五 | wǔ |

| 6 | 六 | liù |

| 7 | 七 | qī |

| 8 | 八 | bā |

| 9 | 九 | jiǔ |

| 10 | 十 | shí |

Once you've got these memorised, you're well on your way to tackling the rest of the system.

The Two Ways to Say Two

One of the very first hurdles for new learners is figuring out when to use the two different words for "two": 二 (èr) and 两 (liǎng). While they both mean "two," they are definitely not interchangeable. Using the wrong one is a classic beginner mistake that can instantly give you away.

A good rule of thumb is that 二 (èr) is for abstract counting and sequences, while 两 (liǎng) is for quantifying physical objects.

Think of 二 (èr) as the digit '2' itself. You use it when the number is just a label or part of a sequence, not when you're actually counting a physical amount of something.

- Phone Numbers: My number is 123... (yī èr sān...)

- Dates: February is 二月 (èryuè).

- Ordinal Numbers: Second place is 第二名 (dì-èr míng).

On the other hand, 两 (liǎng) is what you use when you're talking about "a quantity of two" things. It almost always pops up just before a measure word (which we'll get into a bit later).

- Counting People: two people (两个人 - liǎng ge rén)

- Counting Items: two books (两本书 - liǎng běn shū)

- Counting Money: two yuan (两块 - liǎng kuài)

Getting this distinction right is a massive step toward sounding more natural. To really make concepts like this stick, it helps to integrate effective adult learning principles into your study routine. The goal is to make these foundational numbers feel completely intuitive—that’s the real key to unlocking the entire system of numbers in Mandarin Chinese.

Building Larger Numbers Like a Pro

Right, once you've got one to ten down, you’ve honestly done the hardest part. Making bigger numbers in Mandarin isn't about memorising a bunch of new words; it’s all about logically stacking the ones you already know. Think of it like building with LEGO blocks – simple, predictable, and actually quite satisfying.

The system is so beautifully consistent that once you spot the pattern, you'll be able to build any number up to 99 in no time. For many learners, this is one of those 'aha!' moments where things just click.

From Eleven to Nineteen

Let's start with the teens, from eleven to nineteen. The pattern couldn't be simpler: it's just ten (十, shí) plus the digit. Rather than learning a unique word for each number, you just combine what you already know.

For example, the number eleven is literally "ten-one." You just pop the character for ten, 十 (shí), in front of the character for one, 一 (yī). That's it.

- 11: 十一 (shíyī) — ten-one

- 12: 十二 (shíèr) — ten-two

- 15: 十五 (shíwǔ) — ten-five

- 19: 十九 (shíjiǔ) — ten-nine

This straightforward "ten + digit" formula covers all the teens, making them a breeze to form as long as you're solid on your numbers from one to ten.

Crafting Multiples of Ten

The logic flows just as smoothly for multiples of ten, like 20, 30, 40, and so on. This time, the formula flips slightly to digit + ten. You’re basically just saying how many "tens" you have.

So, to say twenty, you say "two-ten." Thirty is "three-ten," and this pattern holds all the way up to ninety.

- 20: 二十 (èrshí) — two-ten

- 30: 三十 (sānshí) — three-ten

- 50: 五十 (wǔshí) — five-ten

- 90: 九十 (jiǔshí) — nine-ten

Now that you can form the teens and the multiples of ten, putting them together is the next logical step. You just combine the two pieces: twenty (二十) and five (五) become twenty-five (二十五). Simple.

The core pattern for any two-digit number is (Digit) + Ten + (Digit). For example, 47 is simply "four-ten-seven," or 四十七 (sìshíqī).

Expanding into the Hundreds

To push into the hundreds, you only need one new character: 百 (bǎi), which means "hundred." The construction method follows the same logical pattern you’ve just been using. You say how many hundreds you have, then add the rest of the number.

The structure is (Digit) + Hundred + (Rest of the number).

- 100: 一百 (yìbǎi)

- 200: 二百 (èrbǎi) or 两百 (liǎngbǎi)

- 345: 三百四十五 (sānbǎi sìshíwǔ) — three-hundred four-ten-five

The only new rule you need to watch out for comes when a zero appears in the middle of a number, like in 105. In these cases, you have to explicitly voice the zero using 零 (líng).

You simply place 零 (líng) where the zero digit sits. This is a non-negotiable rule and a dead giveaway for someone who hasn't quite got the hang of it yet.

- 105: You say "one-hundred zero five" — 一百零五 (yìbǎi líng wǔ)

- 602: This becomes "six-hundred zero two" — 六百零二 (liùbǎi líng èr)

However, if a number ends in zero, like 150, you do not add 零 (líng) at the end. You just say "one-hundred five-ten."

- 150: 一百五十 (yìbǎi wǔshí)

- 890: 八百九十 (bābǎi jiǔshí)

By remembering these simple, stackable rules, you can confidently piece together any number up to 999. This systematic approach is a huge reason why learners can get comfortable with numbers in Chinese Mandarin surprisingly quickly.

Counting into the Thousands and Beyond

Once you get past 999, you’ll hit the single biggest difference in how Mandarin groups large numbers. It requires a small mental shift, but once you get it, the logic is just as consistent as everything else you’ve learned. For many learners, this is a real lightbulb moment.

Mandarin's system for large numbers is built around groups of ten thousand, rather than one thousand.

Meet the Key Players for Large Numbers

To build numbers into the thousands and beyond, you only need to add three new characters to your arsenal. Think of these as the major milestones on the Mandarin counting highway.

- 千 (qiān): Thousand (1,000)

- 万 (wàn): Ten Thousand (10,000)

- 亿 (yì): Hundred Million (100,000,000)

You might have noticed there isn't a unique character for "million" or "billion". That’s because these numbers are built using 万 (wàn) as the foundation. Getting this concept down is your ticket to talking about everything from city populations to company profits.

The Big Shift: Thinking in Ten Thousands

Imagine you’re counting a huge pile of money. To think in Mandarin, you need to start making stacks of 10,000. This is your new base unit for all bigger numbers.

The core idea is to count how many "ten thousands" (万, wàn) you have. This is the fundamental rule for understanding large numbers in Chinese Mandarin.

Let's see this in action. The number 10,000 is simply 一万 (yī wàn), which literally means "one ten-thousand." Easy enough.

The real test comes with a number like 100,000. You have to ask yourself, "How many stacks of 10,000 are in 100,000?" The answer is ten.

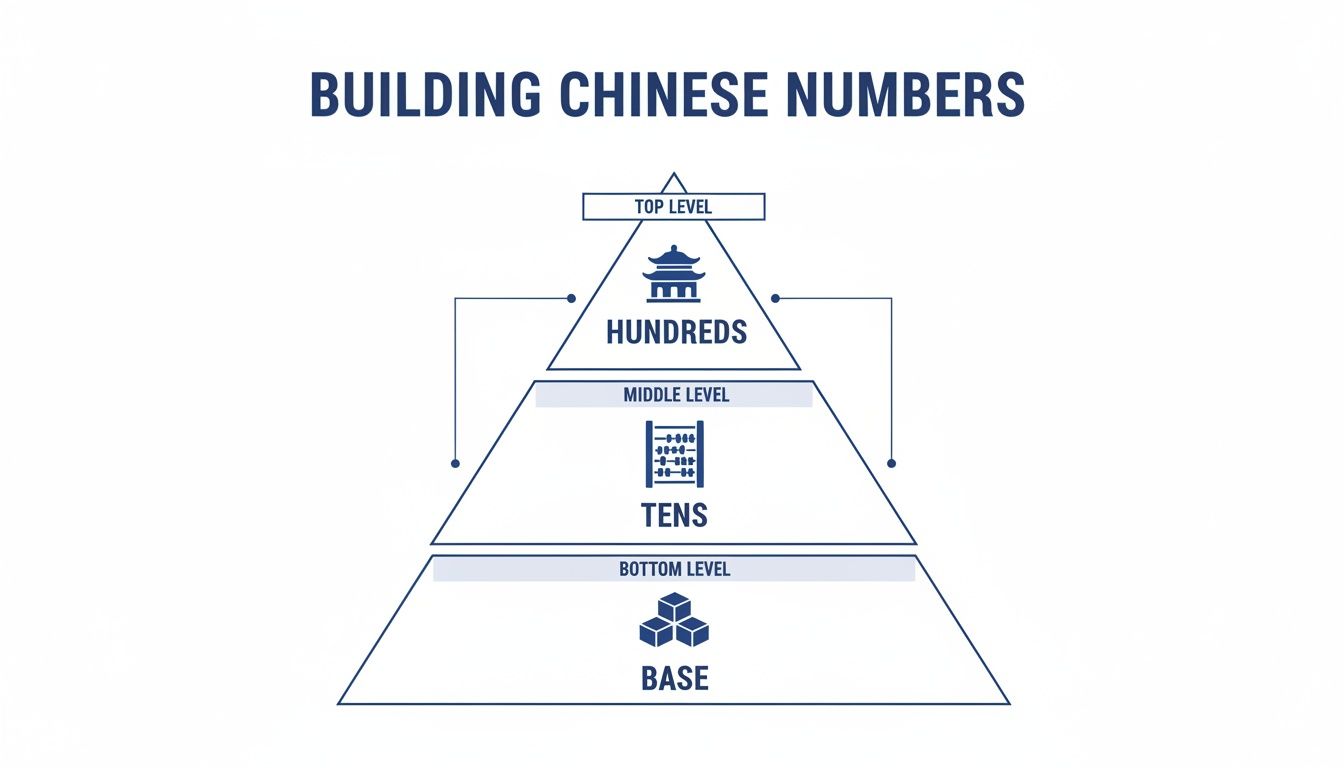

So, 100,000 becomes 十万 (shí wàn) — literally "ten ten-thousands." It's perfectly logical, but it forces you to think inside the Mandarin framework. The diagram below shows how Chinese numbers are built up layer by layer.

This pyramid shows the structured, block-by-block way numbers are formed, with each tier building on the one below it. Once this clicks, putting together even massive numbers feels like a simple assembly job.

How Large Numbers Work in Mandarin

A side-by-side comparison is often the best way to make this concept stick. The table below lays out how the grouping system works for key numbers, which should help the pattern jump out at you.

| Numeral | English Name | Mandarin Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | One thousand | 一千 (yī qiān) |

| 10,000 | Ten thousand | 一万 (yī wàn) |

| 100,000 | One hundred thousand | 十万 (shí wàn) |

| 1,000,000 | One million | 一百万 (yìbǎi wàn) |

| 10,000,000 | Ten million | 一千万 (yīqiān wàn) |

| 100,000,000 | One hundred million | 一亿 (yī yì) |

The table really highlights that pivot point at 10,000. From there, Mandarin just keeps counting in units of 万 (wàn) right up until it hits the next big milestone, 亿 (yì).

A great way to practise is by taking large numbers you see every day—like the price of a car or a house—and trying to say them in Mandarin. For example, a price tag of 45,000 would be 四万五千 (sì wàn wǔ qiān), or "four ten-thousands, five thousand." You can drill these patterns and make them second nature by creating custom sentence packs in the Mandarin Mosaic app, helping you internalise this new way of thinking for good.

Using Numbers in Everyday Chinese Conversations

Knowing how to build numbers is a huge step, but the real magic happens when you start using them in actual conversations. This is where those abstract concepts you’ve been learning become practical, everyday tools. From checking the time to buying a coffee, numbers are woven into the very fabric of daily life.

Putting your knowledge of numbers in Chinese Mandarin into practice is the fastest way to make it stick. Let’s walk through some of the most common situations you’ll find yourself in, starting with the basics like telling the time.

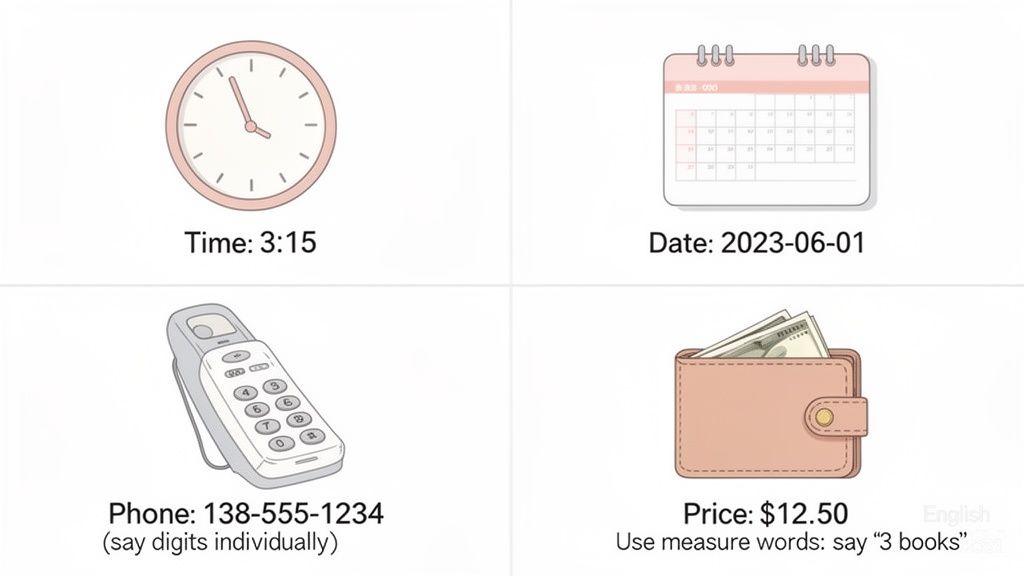

Telling the Time and Date

Thankfully, telling the time in Mandarin is refreshingly straightforward. You only need two key characters: 点 (diǎn) for the hour and 分 (fēn) for the minute. The structure couldn’t be simpler: Number + 点 + Number + 分.

- 3:15 becomes 三点十五分 (sān diǎn shíwǔ fēn).

- 7:30 is 七点三十分 (qī diǎn sānshí fēn).

Handling dates follows a "biggest to smallest" logic. You always start with the year, then the month, and finally the day.

- 年 (nián): Year

- 月 (yuè): Month

- 日 (rì): Day (this is more formal) or 号 (hào): Day (much more common in conversation)

So, December 25, 2024, would be said as 二〇二四年十二月二十五号 (èr líng èr sì nián shí'èr yuè èrshíwǔ hào). Did you notice how the year is read out digit by digit? That's a key detail to remember.

Reciting Phone Numbers

When you’re rattling off a phone number or any long string of digits, you just say each number one by one. But there’s a crucial exception here that you won’t find anywhere else.

To avoid any mix-ups between the sounds of 一 (yī) and 七 (qī), especially over a crackly phone line, the number one is almost always pronounced as 幺 (yāo) instead.

This special use of 幺 (yāo) is a practical little hack for clarity. A phone number like 138-1234-5678 would be read aloud as "yāo sān bā, yāo èr sān sì, wǔ liù qī bā."

It’s also worth noting that for phone numbers, "two" is always read as 二 (èr), never 两 (liǎng).

Talking About Money

When it comes to prices, you’ll hear both formal and colloquial terms. The official unit of currency is the 元 (yuán). In day-to-day life, though, you'll almost exclusively hear people use its slangy counterpart, 块 (kuài).

You can use either, but 块 (kuài) is far more common on the street.

For example, if something costs ¥99.80, you’d hear it as 九十九块八 (jiǔshíjiǔ kuài bā). The final zero is usually just dropped. If you're curious about the cultural side of numbers and pricing, check out our deep dive into the meaning of the number 8 in Chinese culture.

Counting Objects with Measure Words

This brings us to one of the most important concepts in Mandarin grammar: measure words (量词 liàngcí). This concept is sometimes applied in English, like with "a pair of shoes" or "a slice of pizza." Mandarin just takes this idea and applies it to pretty much every noun.

You can't just say "three books." You have to slot the correct measure word between the number and the noun. This formula is non-negotiable: Number + Measure Word + Noun.

- Incorrect: 三书 (sān shū)

- Correct: 三本书 (sān běn shū) — Three [measure word for bound items] books

While there are hundreds of measure words, you can get by perfectly well in most situations with just a handful of the most common ones. The most useful of all is 个 (gè), a general-purpose measure word that works for people, abstract ideas, and many objects when you don’t know the specific one.

- 一个人 (yī ge rén) – One person

- 三个月 (sān ge yuè) – Three months

- 五个苹果 (wǔ ge píngguǒ) – Five apples

Getting your measure words right is a true hallmark of a proficient speaker. It feels a bit strange at first, but with practice, it’ll become second nature and make your spoken Mandarin sound much more authentic.

Going Deeper: Sounding Like a Native Speaker

Knowing the building blocks of Mandarin numbers will get you pretty far, but it's the little details that really make the difference. This is where you move past just counting and start using numbers with the kind of natural ease and cultural savvy that separates a learner from a fluent speaker.

Let's dive into the concepts that will give your Mandarin that authentic edge, from ordinal numbers to those colloquial shortcuts you hear on the street. Mastering these adds a whole new layer to your understanding. You’ll not only get what is being said but also the cultural context sitting just beneath the surface.

From Counting to Ranking: Ordinal Numbers

Turning a regular number into an ordinal one (like 'first', 'second', 'third') is refreshingly simple in Mandarin. You only need one new character: 第 (dì). Just pop it right before the number, and you're good to go.

This straightforward prefix is a huge relief for Mandarin learners.

- First: 第一 (dì yī)

- Second: 第二 (dì èr)

- Tenth: 第十 (dì shí)

- One hundredth: 第一百 (dì yībǎi)

You can use this for just about anything, from ranking competitors in a race (第一名, dì yī míng – first place) to telling someone you live on the third floor (第三楼, dì sān lóu).

Talking Parts and Wholes: Fractions and Percentages

Fractions and percentages can look a bit intimidating at first, but they follow a beautifully logical pattern. The key is the phrase ...分之... (...fēn zhī...), which you can think of as meaning "...parts of...".

The trick is to remember the order is flipped. You say the denominator (the whole) first, then 分之 (fēn zhī), and finish with the numerator (the part).

The Mandarin Fraction Formula: Denominator + 分之 (fēn zhī) + Numerator

So, the fraction "one-third" (1/3) becomes 三分之一 (sān fēn zhī yī). It literally means "of three parts, one." Need to say "three-fifths" (3/5)? Easy: 五分之三 (wǔ fēn zhī sān).

Percentages work exactly the same way, but the denominator is always 百 (bǎi), or 'hundred'. This makes 25% simply 百分之二十五 (bǎi fēn zhī èrshíwǔ) — "of one hundred parts, twenty-five."

Common Colloquialisms and Shortcuts

In day-to-day conversation, native speakers love their shortcuts. One of the most common ones you'll hear involves the number two. Instead of always saying 两个 (liǎng ge) for "two of something," people often just say 俩 (liǎ).

It's a neat little contraction of liǎng and ge, and slipping it into your speech will make you sound much more natural. For example, "the two of us" is simply 我们俩 (wǒmen liǎ).

The Cultural Significance of Numbers

Finally, you can't really master numbers in Mandarin without understanding the cultural superstitions that come with them. In Chinese culture, some numbers are seen as lucky or unlucky based on what other words they sound like. The most famous example is the number four.

The word for four, 四 (sì), sounds almost identical to the word for death, 死 (sǐ). Because of this, it's pretty common for buildings to skip the fourth floor entirely. This is a perfect example of why getting your tones right is so important; you can brush up on your skills with our complete guide to Chinese tones.

This cultural layer is essential for anyone serious about the language. In fact, Mandarin's global importance is growing fast. A British Council's 2023 report highlighted its rising prominence in UK schools, reflecting a growing understanding that these skills are important for global communication.

Got Questions About Chinese Numbers? Let's Clear Them Up.

As you dive deeper into Mandarin, you’ll start running into the same questions that trip up nearly every learner. They're the classic hurdles, but once you clear them, your confidence with numbers will skyrocket. This section is all about tackling those tricky questions head-on.

Think of it as your troubleshooting guide for the most common sticking points. By untangling these confusing areas now, you'll be able to use numbers in Chinese Mandarin far more naturally when you're actually talking to people.

What's the Real Difference Between 二 (èr) and 两 (liǎng)?

This is probably the number one question for anyone learning Mandarin numbers. They both mean "two," but you absolutely cannot swap them. Getting this right is a huge signal that you're moving beyond the beginner stage.

The simplest way to think about it is that 二 (èr) is for abstract digits, while 两 (liǎng) is for counted quantities. You’ll use 二 (èr) when a number is acting like a label—think dates, phone numbers, or rankings.

- February: 二月 (èryuè)

- Second Place: 第二名 (dì-èr míng)

- Floor 22: 二十二楼 (èrshí'èr lóu)

On the other hand, you'll almost always use 两 (liǎng) when you're counting how many of something there are. It pops up right before a measure word.

Here's a quick mental check: if you're answering the question "How many?", you're going to need 两 (liǎng). 'Two people' is always 两个人 (liǎng ge rén), never '二个人'.

It's also the go-to for bigger units like 'hundred', 'thousand', and 'ten thousand'. For example, 200 is almost always said as 两百 (liǎngbǎi).

Why Is the Number 4 Considered Unlucky in Chinese Culture?

This common superstition is all about how words sound. In Mandarin, the number four, 四 (sì), sounds almost exactly like the word for "death," 死 (sǐ). The only thing separating them is the tone.

Because of that grim association, the number four is avoided everywhere in daily life across China and other parts of East Asia. It’s incredibly common for buildings to skip the 4th, 14th, and 24th floors.

Flipping that around, the number eight, 八 (bā), is seen as incredibly lucky. Why? Because its pronunciation is very similar to the word 发 (fā), which means "to prosper" or "get wealthy." That’s why you’ll see people pay a premium for phone numbers and licence plates loaded with eights.

How Do I Say a Phone Number in Mandarin?

Reading out a phone number or any long string of digits in Mandarin is pretty straightforward: you just say each number one by one. But there's a huge exception that every learner needs to lock in.

The number one, 一 (yī), is almost always pronounced as 幺 (yāo) when reading digits like this. This is purely for clarity. Over a bad phone line, the sound of yī is just too easy to mix up with the sound of seven, 七 (qī).

So, a phone number like 138-1234-5678 would be read out as "yāo sān bā, yāo èr sān sì, wǔ liù qī bā." Notice that for 'two', you always stick with 二 (èr) in this context—never 两 (liǎng).

What Are Measure Words and Why Are They So Important?

Measure words, or 量词 (liàngcí), are a core part of Mandarin grammar. In some other languages, you might see similar concepts like "a slice of bread" or "a pair of trousers," but Mandarin uses a specific classifier for nearly every single noun you count.

The structure is non-negotiable: Number + Measure Word + Noun. You can't just say "three books" as '三书 (sān shū)'. You have to slot in the correct measure word, which for books is 本 (běn). The correct phrase is 三本书 (sān běn shū).

The most common, all-purpose measure word is 个 (gè). It’s your best friend when you’re not sure which specific one to use for people, places, or common objects. Learning the most frequent measure words is absolutely essential if you want your Chinese to sound correct and fluent.

Ready to stop just memorising words and start seeing how they work in real sentences? Mandarin Mosaic is designed to help you internalise these patterns naturally. Instead of drilling isolated vocabulary, you'll learn in context, making concepts like measure words and number usage feel intuitive. Check out https://mandarinmosaic.com to see how sentence mining can transform your study routine.