Unlocking Chinese Four Character Idioms: A Practical Guide for Fluent Mandarin

Ever feel like you’ve hit a wall with your Mandarin? You can get by in daily conversations, but when you try to express a deeper, more complex idea, it just feels… clunky. This is a common hurdle, and the key to clearing it often lies in mastering one of the most elegant features of the language: Chinese four-character idioms.

These compact phrases, known as 成语 (chéngyǔ), are much more than just vocabulary. Think of them as high-resolution pixels that add depth and clarity to your linguistic picture. While a basic sentence can paint a scene, a well-placed Chengyu adds vibrant colour, texture, and emotion that simple words just can't match.

What Are Chengyu and Why Do They Matter?

Imagine trying to explain a complex idea like 'a blessing in disguise' using only the simplest words. It’s possible, but it’s not very efficient. Chengyu are Mandarin’s answer to this—powerful linguistic shortcuts packed with history, fables, and ancient wisdom. They aren't just vocabulary; they're cultural DNA, making conversations richer and far more nuanced.

The Soul of the Language

Each Chengyu is like a miniature time capsule. Most are rooted in classical literature, famous historical events, folklore, or philosophical teachings, carrying centuries of cultural context in just four characters. Their structure is fixed—you can't swap out words—which makes them instantly recognisable and impactful.

Take the idiom 井底之蛙 (jǐng dǐ zhī wā), for example. It translates to "a frog at the bottom of a well." Thanks to a classic fable, this phrase instantly paints a vivid picture of someone with a narrow, limited perspective. It’s concise, memorable, and deeply cultural.

This is why learning Chengyu is about more than just memorising phrases. It’s about connecting with the stories and values that have shaped Chinese culture for millennia. Many Mandarin learners find that idioms are a key reason for pushing past the intermediate plateau.

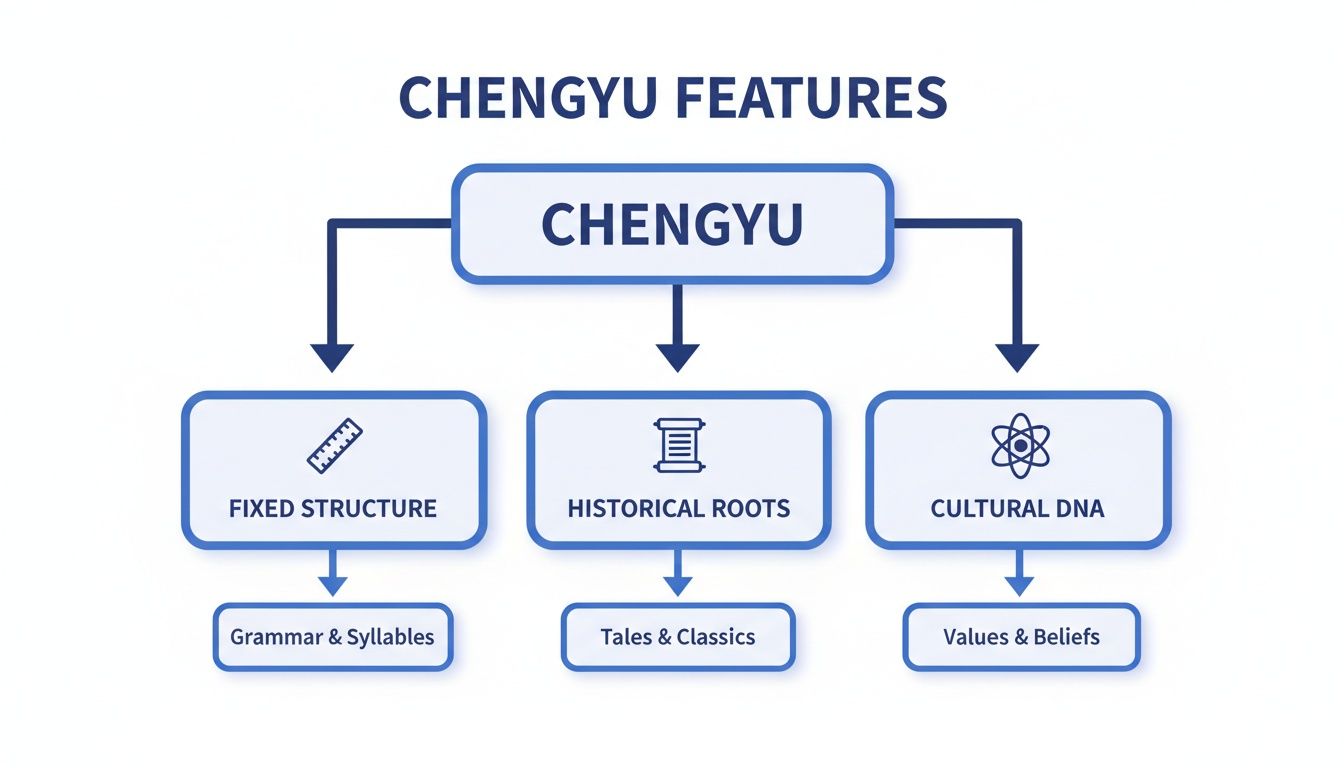

To help you get a clearer picture, here’s a quick breakdown of what makes a Chengyu a Chengyu.

Core Features of Chinese Four Character Idioms

A quick look at the defining characteristics of Chengyu to build your foundational understanding.Characteristic Description Example Idiom Fixed Structure Always consists of four characters. The order and characters cannot be changed. 画蛇添足 (huà shé tiān zú) - "Draw a snake and add feet." Concise Meaning Conveys a complex idea, story, or moral in just four syllables. 对牛弹琴 (duì niú tán qín) - "Play the zither to a cow." Classical Origins Most originate from ancient texts, historical events, myths, or fables. 守株待兔 (shǒu zhū dài tù) - "Guard a tree stump waiting for a hare." Figurative Language The literal meaning is often different from the implied, figurative one. 胸有成竹 (xiōng yǒu chéng zhú) - "Have a fully-formed bamboo in one's chest."

Understanding these features is the first step to appreciating just how powerful these little phrases can be.

Why Chengyu Are Essential for Fluency

Integrating Chengyu into your vocabulary is a clear sign you’re moving beyond textbook Mandarin. It shows a sophisticated grasp of the language and an appreciation for its cultural subtleties. Using them correctly allows you to:

- Communicate with Precision: Express complex ideas concisely and powerfully.

- Sound More Natural: Speak in a way that resonates more closely with native speakers.

- Understand Cultural Nuances: Grasp the subtext in conversations, literature, and media.

Ultimately, Chengyu are the bridge between being a competent speaker and a truly fluent one. They unlock a richer, more poetic dimension of the language that is essential for deep communication. To deepen your understanding of the broader linguistic context for these idioms, you might explore resources on topics like Exploring Mandarin Chinese. By embracing them, you’re not just learning words—you’re learning to think in a new, more nuanced way.

Decoding the Structure of Four‑Character Idioms

At first glance, chengyu might just look like four characters squashed together. How can they possibly tell a whole story or teach a profound lesson? The magic is in their surprisingly elegant and logical structure. They aren't random at all; they follow clear grammatical patterns that, once you spot them, are like a key unlocking their meaning.

Getting a handle on these patterns is a genuine game-changer. It helps you shift from frustrating literal translations to a much more intuitive feel for the idiom’s real message. Instead of seeing a linguistic puzzle, you start to see a solvable equation.

This flowchart breaks down the three core features that give chengyu their unique power and form.

As you can see, the fixed structure is the bedrock. It's the framework that holds the history and cultural meaning together.

Common Grammatical Patterns

The good news is that many chengyu follow grammatical rules that are very similar to modern Mandarin. This makes them far more approachable than you might think. Recognising these structures helps you deconstruct the idiom and get to its logical heart.

Here are a few of the most common patterns you'll run into:

- Verb-Object: This is one of the most straightforward types. The first character or two act as a verb, and the last one or two are the object. Take 画蛇添足 (huà shé tiān zú). 画 (huà – to draw) is the verb and 蛇 (shé – snake) is the object. The second half, 添足 (tiān zú – add feet), follows the exact same pattern.

- Subject-Predicate: Here, the first part is the subject, and the second part tells you what the subject is or what it's doing. A brilliant example is 胸有成竹 (xiōng yǒu chéng zhú), which literally means "chest has completed bamboo". The subject is the chest (representing the mind), and the predicate tells us it already contains the finished masterpiece.

- Modifier-Noun: This structure uses the first part to describe or modify the second part. Think of 井底之蛙 (jǐng dǐ zhī wā), or "a frog at the bottom of a well". The phrase 井底 (jǐng dǐ – bottom of the well) acts like an adjective, modifying the noun 蛙 (wā – frog).

The Power of Parallelism

Beyond these basic structures, many of the most memorable and beautiful chengyu use something called parallelism. This is where the first two characters form a phrase that mirrors the last two, either in meaning, structure, or both. It creates a lovely sense of balance and rhythm, almost like a miniature poem.

A huge chunk of chengyu have this kind of internal symmetry. In fact, linguistic analysis shows that a massive 40.8% have a semantically parallel structure. This gives them a rhetorical punch that makes them much easier to remember. You can read more about these linguistic findings and how they impact learning.

Just look at the idiom 山穷水尽 (shān qióng shuǐ jìn). Here, 山 (shān – mountains) is parallel to 水 (shuǐ – water), and 穷 (qióng – exhausted) is parallel to 尽 (jìn – used up). This structure paints a powerful picture of reaching the absolute end of your options, with nowhere left to turn.

By learning to spot these underlying patterns—from simple verb-object pairs to these more sophisticated couplets—you’re building a framework for understanding any new idiom you come across. It stops being a daunting memory test and starts feeling more like a fascinating puzzle you actually know how to solve.

Exploring Chengyu Through Stories and Examples

The absolute best way to get Chinese four-character idioms to stick isn't by grinding out flashcards. It’s by digging into the fantastic stories behind them. Think of each chengyu as a tiny cultural time capsule—a snapshot of a historical event, a moral from an ancient fable, or a nugget of philosophical wisdom.

When you understand where these phrases come from, they stop being abstract characters and transform into memorable, practical tools for conversation. It feels less like studying a dictionary and more like uncovering the tales that have shaped the Chinese language over thousands of years.

Let's dive into some of the most common chengyu you'll hear, grouped by the type of story they came from. For each one, we’ll look at its real meaning, its origin, and a natural example sentence to see how it’s used in the wild.

The table below gives a quick overview of some popular idioms, their backstories, and what they really mean.

Common Chengyu Examples and Their Origins

| Chengyu (Pinyin) | Literal Translation | Actual Meaning | Origin Story Snippet |

|---|---|---|---|

| 四面楚歌 (sì miàn chǔ gē) | Four sides, Chu songs | To be surrounded by enemies; isolated and helpless. | An army surrounded its enemy and sang their folk songs, crushing their morale. |

| 纸上谈兵 (zhǐ shàng tán bīng) | On paper, discuss soldiers | Armchair strategising; great in theory, useless in practice. | A general who only knew theory from books led his army to a disastrous defeat. |

| 守株待兔 (shǒu zhū dài tù) | Guard stump, wait for rabbit | To wait foolishly for a lucky break instead of working for it. | A farmer stops working, hoping another rabbit will accidentally run into a stump. |

| 拔苗助长 (bá miáo zhù zhǎng) | Pull seedlings, help grow | To spoil something by being too impatient to rush its natural growth. | An impatient farmer pulls on his seedlings to make them taller, killing them all. |

| 塞翁失马 (sài wēng shī mǎ) | Old man at the frontier loses his horse | A blessing in disguise; what seems like bad luck might be good. | A Daoist tale of an old man whose apparent misfortunes lead to good outcomes. |

Let's break these down a bit further.

Idioms From Historical Events

So many of the most vivid chengyu are ripped straight from the pages of Chinese history. These idioms capture a specific moment or strategy from a real event, giving them a strong narrative hook that makes them much easier to remember.

1. 四面楚歌 (sì miàn chǔ gē)

This phrase literally translates to "four sides, Chu songs," and it paints quite a picture. It means to be completely surrounded by enemies, isolated, and helpless.

It comes from the fall of the Chu Kingdom. The Han army had the last of the Chu forces cornered and, in a clever move, had their own soldiers sing folk songs from the Chu region. Hearing songs from home, the Chu soldiers’ will to fight just collapsed, assuming their homeland had already been conquered.

Example Sentence:

由于公司的重大失误,他现在四面楚歌,不知道该怎么办。

(Yóuyú gōngsī de zhòngdà shīwù, tā xiànzài sì miàn chǔ gē, bù zhīdào gāi zěnme bàn.)

"Due to the company's major mistake, he is now completely surrounded and helpless and doesn't know what to do."

2. 纸上谈兵 (zhǐ shàng tán bīng)

Literally "on paper, discuss soldiers," this one is for all the armchair generals out there. It means to engage in theoretical discussion that is completely useless in a real situation.

The story behind it is about a general from the state of Zhao who had only ever studied military strategy from books. When he was finally given command of a real army, his total lack of practical experience led to a catastrophic defeat. We all know someone like that, right?

Example Sentence:

他的计划听起来不错,但只是纸上谈兵,完全不切实际。

(Tā de jìhuà tīng qǐlái bu cuò, dàn zhǐshì zhǐ shàng tán bīng, wánquán bù qiè shíjì.)

"His plan sounds good, but it's just armchair strategising and completely impractical."

Idioms From Ancient Fables

Fables and folklore are another treasure trove for chengyu, often using simple stories about animals or farmers to teach a deep moral lesson. These are often the first idioms Chinese children learn because the stories are so sticky.

1. 守株待兔 (shǒu zhū dài tù)

This idiom translates to "guard stump, wait for rabbit." Its real meaning is to foolishly wait for a stroke of pure luck instead of putting in the work.

The tale is about a farmer who sees a rabbit accidentally run full-pelt into a tree stump and die. Thrilled with his free meal, he abandons his farm work to sit by that same stump every single day, hoping another rabbit will do the same. Of course, it never does.

Example Sentence:

你不应该守株待兔,应该主动去寻找新的工作机会。

(Nǐ bù yìng gāi shǒu zhū dài tù, yīnggāi zhǔdòng qù xúnzhǎo xīn de gōngzuò jīhuì.)

"You shouldn't just wait for a lucky break; you should proactively look for new job opportunities."

2. 拔苗助长 (bá miáo zhù zhǎng)

The literal meaning here is "pull seedlings, help grow." This idiom perfectly captures the idea of spoiling something by being too impatient and trying to rush its natural development.

It comes from the story of an overeager farmer who wanted his rice seedlings to grow faster. His brilliant idea? To pull on each one to make them a bit taller. The next day, he discovered that all the seedlings had withered and died.

Example Sentence:

让孩子学太多东西是拔苗助长,对他们的发展没有好处。

(Ràng háizi xué tài duō dōngxi shì bá miáo zhù zhǎng, duì tāmen de fāzhǎn méiyǒu hǎochù.)

"Making children learn too many things is spoiling things through impatience and isn't good for their development."

Idioms From Philosophical Teachings

Many chengyu are born from the works of ancient philosophers, packing a core concept into just four elegant characters. These often reflect deep-seated cultural values about wisdom, perspective, and how to look at the world.

1. 塞翁失马 (sài wēng shī mǎ)

This one translates to "the old man at the frontier loses his horse" and means a blessing in disguise. It’s the idea that what seems like bad luck might actually turn out to be good fortune.

The origin is a Daoist text about a man whose horse runs away (bad luck), but then it returns with another excellent horse (good luck!). Then, this new horse throws his son, breaking his leg (bad luck), but this injury saves the son from being drafted into a deadly war (good luck). It’s a classic story about not jumping to conclusions about events.

Example Sentence:

虽然我错过了那班火车,但我因此遇到了一个老朋友,真是塞翁失马。

(Suīrán wǒ cuòguòle nà bān huǒchē, dàn wǒ yīncǐ yù dàole yīgè lǎo péngyǒu, zhēnshi sài wēng shī mǎ.)

"Although I missed that train, I met an old friend because of it. It was truly a blessing in disguise."

Learning these idioms through their stories is the key to making them stick. You’re not just memorising four characters; you're absorbing a piece of culture that makes the meaning intuitive. For anyone serious about this method, check out our guide on the power of sentence mining for language acquisition to take your learning to the next level.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls When Using Idioms

Using a Chinese four-character idiom, or chengyu, can make you sound incredibly fluent. Get it right, and you sound like a local. But get it wrong, and you'll just create confusion.

Nailing these linguistic gems takes more than just rote memorisation. It's about feeling the context, the formality, and the subtle shades of meaning. Let's walk through the common traps that even dedicated students fall into, so you can use chengyu with confidence.

The Dangers of Literal Translation

One of the biggest hurdles for learners is translating an idiom character by character. This almost never works. A chengyu’s power comes from the story behind it, not the sum of its individual parts.

Take 马马虎虎 (mǎ mǎ hū hū). A word-for-word translation gives you "horse horse tiger tiger," which makes absolutely no sense. Its real meaning is "so-so" or "careless." The phrase comes from a story about a sloppy painter whose work looked like neither a horse nor a tiger. Nothing to do with animals at all.

Relying on direct translation strips the idiom of its cultural soul. You need to learn the story or the figurative meaning behind the four characters, not just the definitions of the characters themselves. This shift in approach is fundamental.

To sidestep this common mistake:

- Learn the Story: Whenever you learn a new chengyu, find out the story or fable it comes from.

- Focus on the Concept: Ask yourself, "What feeling or situation does this phrase really describe?"

- Study in Context: Look for multiple example sentences to get a genuine feel for how it's used in the wild.

Mismatching Formality and Context

Another classic error is dropping a highly formal or literary idiom into a casual, everyday chat. You might be trying to sound smart, but you'll probably just come across as stiff or pretentious.

For instance, an idiom like 风华正茂 (fēng huá zhèng mào), meaning "in the prime of one's life," is beautifully poetic. But you wouldn't use it to casually tell a friend they look good. It belongs in a formal speech or a piece of writing praising a group of talented young people.

This kind of contextual awareness is what separates okay speakers from great ones. If you want to dig deeper into how language choices shape our interactions, you can find some fantastic insights on improving communication with language.

Practical Tips to Use Chengyu Correctly

Becoming truly skilled with Chinese four-character idioms is a slow-burn process. It’s not about knowing hundreds of them. It's about mastering a smaller, useful collection and knowing exactly when to deploy them.

Before you use a chengyu, run through this quick mental checklist:

- Do I know the real meaning? Am I certain it’s not just the literal translation?

- Is this the right situation? Is the tone of this conversation right for this particular idiom?

- Will my audience get it? Am I talking to someone who will appreciate this, or will it just fly over their head and cause confusion?

- Have I heard a native speaker use it this way? Try to stick to using idioms in ways you've already heard in real conversations or seen in media.

Keep these points in mind, and you'll move from just knowing idioms to using them with the skill and precision of a fluent speaker.

A Smarter Way to Learn and Remember Chengyu

Traditional methods for learning Chinese four character idioms often feel like a marathon of brute-force memorisation. We’ve all been there, staring at endless flashcard drills and long vocabulary lists. It can be pretty disheartening, turning a fascinating part of the language into a real chore.

But what if there was a more effective, brain-friendly way to make these powerful phrases stick?

The secret is to stop memorising idioms in isolation and start learning them in context. Our brains are wired to remember stories and connections, not just random bits of data. This is where a powerful method called sentence mining comes into play—it’s all about finding idioms in real-world sentences and studying them as a complete thought.

This approach ensures you not only learn what a chengyu means but also get an intuitive feel for how it’s used, its tone, and its place in a sentence. When you see an idiom used naturally, it registers far more deeply than a simple dictionary definition ever could.

Contextual Learning Through Sentence Mining

Instead of just drilling 画蛇添足 (huà shé tiān zú) on its own, imagine learning it through a sentence like this: “你的报告已经很好了,再加这些细节就是画蛇添足了。(Your report is already excellent; adding these details would be like drawing legs on a snake.)”

Suddenly, the idiom has life. You understand it means "to ruin something by overdoing it" and you see exactly how to drop it into a conversation.

This is the core idea behind modern language learning tools. An app like Mandarin Mosaic, for example, automates this whole process. It introduces new words and idioms within carefully chosen sentences, making sure you absorb vocabulary naturally without feeling swamped. You see the idiom in action from day one.

Learning in context isn't just more engaging; it's scientifically more effective. Seeing a word or phrase in a complete sentence creates stronger neural connections, dramatically improving long-term recall compared to studying isolated words.

This method transforms learning from a passive chore into an active process of discovery. For an even deeper dive into smart learning, it's worth checking out proven methods like the Feynman Technique, which is all about explaining concepts in simple terms to really cement your own understanding.

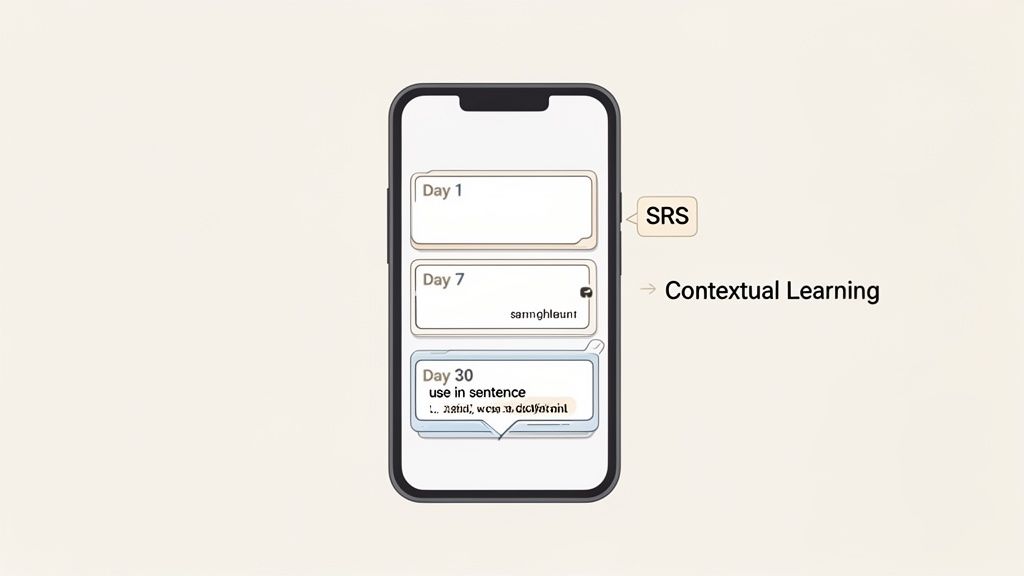

Automating Retention with Spaced Repetition

Okay, so learning an idiom in context is the first step. But how do you make sure you don't forget it a week later? The answer lies in combining sentence mining with a Spaced Repetition System (SRS). This is basically an algorithm that schedules reviews at the perfect moment—just before you’re about to forget something.

An SRS shows you a sentence with a chengyu more frequently at first, then gradually increases the time between reviews as it moves into your long-term memory. It's an evidence-based technique that’s far more efficient than old-school cramming.

Here’s how this powerful combination works in practice:

- Initial Encounter: You learn a new idiom, like 对牛弹琴 (duì niú tán qín), inside a sentence that makes its meaning ("to play the zither to a cow," i.e., to address the wrong audience) crystal clear.

- Smart Scheduling: The SRS algorithm schedules your first review for the next day. If you get it right, your next review might be in three days, then a week, then a month.

- Effortless Recall: Over time, the idiom becomes a permanent part of your active vocabulary, ready to be used correctly whenever you need it.

Platforms like Mandarin Mosaic build this SRS technology directly into the learning experience. The app automatically tracks your progress and schedules reviews for you, taking all the guesswork out of studying. This system helps integrate Chinese four-character idioms into your vocabulary so they feel like a natural part of your speech. You can learn more about how spaced repetition supercharges language learning and see why it's a cornerstone of any effective study plan.

By ditching the rote drills for contextual learning and SRS, you’re not just studying smarter; you're building a deeper, more intuitive connection with the language. This ensures you can actually recall and use chengyu correctly, adding that extra layer of nuance and authenticity to your Mandarin.

Your Chengyu Journey Starts Now

To really get the hang of Mandarin, you have to look beyond single words and dive into the culture. Chinese four-character idioms are your ticket to that world. We've walked through what they are, how they're pieced together, and the best ways to learn them—moving you from rote memorisation to real, lasting understanding. The path from just getting by to speaking fluently is paved with these powerful, story-packed phrases.

The big takeaway? Don't treat chengyu like a vocabulary list you have to cram. Think of them as mini-stories to be unpacked in context. Each one holds a history lesson, a moral from an ancient fable, or a snippet of timeless wisdom. This mindset shifts learning from a chore into a genuinely fascinating cultural exploration.

Turning Knowledge into Action

By focusing on the structure, the story, and the right study tools, you can add incredible depth, colour, and flair to your Mandarin. It’s about more than just padding your vocabulary; it’s about connecting with the very heart of the language.

Here’s how you can start doing this today:

- Context is King: Always learn idioms inside a full sentence. This is the only way to see how they actually work in the wild.

- Embrace the Story: Take a minute to learn the tale behind each idiom. That narrative hook will be your best friend for making it stick.

- Use Smart Tools: Get technology on your side. Tools that mix contextual learning with Spaced Repetition will make your study time so much more effective.

Your goal isn't to know thousands of obscure idioms. It’s to master a core set of common ones so well that you can drop them into conversation confidently and correctly, making your Mandarin sound that much more natural and expressive.

There’s no better time to put these ideas to work and start discovering the richness of Chinese four-character idioms for yourself. Your journey to a deeper fluency begins with that first story, that first sentence, that first little spark of connection.

Frequently Asked Questions About Chengyu

As you start exploring the world of Chinese four-character idioms, a few questions are bound to pop up. Here are some quick, straightforward answers to the things learners most often wonder about, helping to lock in the key ideas we've covered.

How Many Chengyu Do I Need to Know for Fluency?

There’s no magic number here, and honestly, quality beats quantity every time. To hold your own in conversations, getting a solid handle on 50 to 100 of the most common idioms will make a massive difference. You'll find yourself expressing nuanced ideas and understanding native speakers much more easily.

If you’re diving into advanced literature or formal documents, though, you’ll want a vocabulary of several hundred. The best way to go about it is to start with a core group and really master how to use them. It’s far better to deeply understand 50 chengyu than to just vaguely recognise 500.

Can I Really Use Chengyu in Daily Conversation?

Absolutely! While some chengyu sound like they belong in ancient poetry, plenty of them are perfect for everyday chats. You’ll hear native speakers drop common idioms all the time to add a bit of colour and precision to what they’re saying.

- 一举两得 (yī jǔ liǎng dé): A common idiom that means getting two benefits from one action.

- 乱七八糟 (luàn qī bā zāo): Meaning "a total mess," it’s perfect for describing a messy room or a chaotic situation.

The trick is to learn them with example sentences so you get a feel for the right tone and context. Pay close attention to how they’re used in films, TV shows, and podcasts – that's how you’ll develop a natural instinct for when to use them.

Should I Prioritise Learning Pinyin or Characters for Idioms?

The honest answer? You need both. They work hand-in-hand to give you the full picture of each idiom. Thinking of it as an either/or choice is a trap.

The characters hold the visual meaning and often link directly to the idiom’s origin story, which is a powerful memory aid for reading. At the same time, Pinyin is absolutely vital for getting the pronunciation and tones right – get those wrong, and you can completely change a phrase's meaning.

The most effective approach is a balanced one. That means learning the characters, Pinyin, audio, and example sentences all at once. This ensures you can recognise, understand, say, and actually use each idiom correctly.

Ready to move beyond just memorising lists and learn Chinese four-character idioms in a way that actually sticks? Mandarin Mosaic uses sentence mining and spaced repetition to help you master vocabulary in context. Start your journey to deeper fluency today at https://mandarinmosaic.com.